I confess, I love end-of-year movie lists. It’s an opportunity to see others’ tastes, personalities, and experiences in a succinct form, as well as an opportunity for me to highlight the true, the good, and the beautiful I’ve found in cinema from the previous 365 days. I’m not a fan of “but what about [film that wasn’t on the list]?” queries, as those seem to miss the point. If it’s not on my list, it’s a) because I didn’t see it, or b) I didn’t like it as much as the films I listed.

I approach such list-making (and list-reading) as a contemplative practice, a way of reflecting upon the year, a sort of filmic autobiography or journal. I watched 275 films in 2018, or about 5-6 per week–you can find my 2018 Film Journal here. This was my first full year as an OFCS film critic, the year I became a Rotten Tomatoes “Tomato-meter Approved” critic, as well as a year of living in Scotland for my PhD research on theology, philosophy, and film. Beyond Cinemayward, I wrote about film for Think Christian, Bright Wall/Dark Room, and Transpositions. Personally, it was a year where our family spent a month in Paris, the year when my three kids all began attending primary school, and a year of diving further into the world of academia. And it’s been a wonderful year in cinema, which is why my usual Top 20 has expanded to a Top 25.

My film-viewing has been significantly shaped by living in Scotland. There were films I saw which never made it to the US (Mary Magdalene) and films I was almost unable to see due to their lack of distribution in the UK (Eighth Grade). Thanks to trips for academic conferences–one to Toronto and another to Denver–I was able to catch a few films in North American theaters which didn’t come to the local indie cinema in St Andrews. Phantom Thread, Lady Bird, and Coco are all excellent films released in the UK in 2018, but would typically be considered 2017 films due to their US release dates (I’ve chosen not to include them here; if I did, Phantom Thread and Lady Bird would both be in my Top 10). I’ve also not included Paddington 2, as it was on my top 20 films of 2017 list. There are also critically-acclaimed films I simply never saw, such as The Favourite, Hereditary, Minding the Gap, Sorry to Bother You, and Can You Ever Forgive Me?. Perhaps one of these will be included here in the future (my top film from 2016 changed from La La Land to Paterson once I saw the latter film).

Here are my top 25 films from 2018, listed in ranked order. If I’ve reviewed the film, I’ve included a link; I’ve also tried to point out where the film is currently available to view. Thanks for reading Cinemayward in 2018, and please keep reading as I celebrate the true, the good, and the beautiful in 2019.

25) To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before (Susan Johnson). A perfect blend of John Hughes teen angst with Disney film teen cheesiness, To All the Boys contains familiar coming-of-age tropes mixed with fresh narrative ideas, especially in its emphasis on sisterly love and how it addresses sexuality and race. With a plethora of such interesting characters involved in romantic triangles (or quadrangles?) and its focus on familial love between sisters, To All the Boys is a Jane Austen-esque rom-com for 21st-century America. Lana Condor and Noah Centineo give excellent performances in the lead roles, with Condor as a beautiful blend of humility and confidence, and Centineo–a Mark Ruffalo clone if ever there was one–coming across as an authentically caring and capable guy. Delightful. (Netflix)

24) Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc (Bruno Dumont). This is The Punk Rock of Joan of Arc, a heavy metal musical about the early years of the cinematic saint. The pious French girl is portrayed by Lise Leplat Prudhomme at age 8 and Jeanne Voisin as a teen; both are perfectly cast, singing and dancing and praying in the vibrant French countryside. Bruno Dumont’s approach is absurd and anachronistic, like a mashup between Robert Bresson’s stilted spiritual cinema and John Carney’s postmodern musicals (Once, Sing Street). This is a film featuring head-banging nuns and a guy who dabs while he semi-raps about God and France. That’s probably not for everyone, but its weirdness won me over. Even when the central conceit starts to feel monotonous, the film remains a joyous and distinct addition to the pantheon of Joan of Arc films. (Amazon Prime US, Kanopy)

23) Chosen: Custody of the Eyes (Abbie Reese). The documentary film project from director Abbie Reese required her to literally put the camera in her subject’s hands and walk away. Thankfully, these hands–Sister Amata, a young cloistered nun living in a monastery in Illinois–are quite capable, and Chosen features some of the most unexpectedly incredible framing and blocking from this year. Shot with handheld digital cameras inside the monastery, the film elicits rich aesthetic and ethical questions about cinema’s capacity to see what is typically unseen, to invite us to witness worlds beyond our experience. In an apt description, Reese called her film “Into Great Silence meets MTV’s The Real World.” (DVD via film website)

22) If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins). A labor of love and a project infused with personal resonance and appreciation, Jenkins’ adaptation of James Baldwin’s novel is a haunting, romantic, and melancholic depiction of the American black experience. The lighting and the score are wondrous, the pacing patiently allowing us to soak in the romantic ambiance Jenkins has created. Lush, woozy and exquisite, Beale Street takes a symphonic approach to its simple narrative: a black man and a black woman are in love, yet separated by injustice in 1970s New York. It’s timely yet timeless. (In Theaters)

21) The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (Joel and Ethan Coen). “Do you engage in divine worship?” It’s a question posted by Zoe Kazan’s character in the fifth of six tales in the Coen brothers’ Western anthology. Yet in this nihilistic world about the inevitability of human mortality, neither Kazan’s question nor any worship can save her. Some aspects are troubling and problematic, such as the film’s depiction of Native Americans or its underlying cynical philosophy. But I wonder if this is intentionally provocative from the mischievous brothers, prompting the viewer to wake up and consider this mortal coil. Bleak, bloody, and darkly hilarious, Ballad is classic Coens, a culmination of all their previous themes captured in colorful digital cinematography. Kazan pronouncing the state name as “Orygun” is everything. (Netflix)

20) Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (Ol Parker). The biggest surprise on my list is a musical sequel I never intended on seeing. But after a snafu at a Parisian cinema where I ended up with a non-refundable ticket, my options were limited. I had not seen the first Mamma Mia! since its release a decade ago (my wife assures me it’s mildly entertaining). But it was 95 degrees outside in Paris, and the air conditioned theatre beckoned, so I figured, why not? And y’know, the film was wonderful. Sheer delight and cinematic optimism, and perhaps the best jukebox musical of the 21st-century. Lily James is simply enchanting, and everyone in the film is clearly having a good time. Their joy is contagious–this film is fun. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

19) A Star Is Born (Bradley Cooper). The fourth version of this story, Bradley Cooper’s passion project is far from shallow. This new iteration on a classic theme is akin to the pop music it both celebrates and critiques: it’s insanely likable, emotionally moving even when you know you’re being manipulated to feel, and strangely inspiring, despite its somewhat unsurprising premise and narrative arc. The first act of A Star is Born has genuinely perfect tempo, hitting all the right emotional beats, culminating in Ally’s first on-stage performance with Jack, one of my favorite scenes from 2018. I’m predicting it now: A Star Is Born wins Best Picture at the 2019 Oscars. (In Theaters)

18) A Quiet Place (John Krasinski). A Quiet Place is nerve-wracking, affecting, frustrating, and life-affirming. In this, it’s a bit like parenthood in general. A film with a monastic ethos, A Quiet Place focuses on a family living a quiet communal life on an isolated farm in the wilderness, going through the rhythms–the daily office–of survival in a silent post-apocalyptic world. They pray silently before sharing a meal together, holding hands in in solidarity. They gather food and do their chores in silent faithfulness. They light beacons at night to shine hope into the darkness, and see other fires signaling in the distance. Even their last name–Abbott–bespeaks of this cloistered lifestyle. In this, a creative and distinct sci-fi thriller is also a spiritual allegory, one worth listening to. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

17) Private Life (Tamara Jenkins). Paul Giamatti and Kathryn Hahn’s portrayal of a couple experiencing infertility is striking in its intimacy and rawness–it could almost feel invasive or voyeuristic, except that Tamara Jenkins’ script and direction are wonderfully sympathetic and caring. The dynamic between Giamatti and Hahn is so sincere, there are moments it feels like a documentary. The humor is sharp and awkward, the cinematography richly captivating. Private Life is a perfect example of Ebert’s empathy-generating machine descriptor for cinema, which is about the highest praise one can give such a film. (Netflix)

16) Summer 1993 (Carla Simón). A cinematic memoir and memorial, Carla Simón has crafted a beautiful film about childhood and grief, imbued with such subtlety and authenticity that it never feels conventional or emotionally manipulative. The film follows a young girl in the wake of her parents’ death and her subsequent life with her relatives in the countryside. It’s a remarkable feature debut for Simón, and the film is currently at 100% on Rotten Tomatoes. Some viewers may find the languid meandering of the narrative to be dull, but I found it to be wonderfully affecting, allowing one to fully appreciate the fullness and detail of the mise-en-scene, and to feel the haunting presence of grief alongside the characters. (Amazon Prime US, Kanopy)

15) First Man (Damien Chazelle). First Man is both an affective celebration of human achievement as well as a stunning cinematic thrill ride. The lead performances from Ryan Gosling and Claire Foy as the Armstrongs in the “space race” ground the human emotions even as the incredible score and cinematography take us to new heights. The realism is palpable and procedural, the detailed symphony of sound and image in perfect harmonious sequence, orchestrated with an engineer’s exactitude while never feeling cold or distant. There were moments when I forgot I was watching a performance of the events rather than the events themselves, as if Damien Chazelle had used a time machine to plant cameras throughout the NASA missions, as if Gosling had somehow become Armstrong. An underseen masterful biopic.

14) Support the Girls (Andrew Bujalski). Andrew Bujalski’s affecting Support the Girls is one of the more authentic, honest, and insightful cinematic depictions of the food industry work environment. Bujalski’s script and direction is skillful, yet the film’s power is (rightly) in the main actresses’ excellent performances–Regina Hall and Haley Lu Richardson are just phenomenal. A biting, disheartening look at the reality of the sexual harassment and misogyny that women continue to experience in the workplace, Support the Girls is also a depiction of the deep resolve and pastoral heart of a good manager like Lisa (Hall). (Available on DVD/Blu-ray)

13) Mary Magdalene (Garth Davis). Navel-gazing and listless, Mary Magdalene is nevertheless an affecting, contemplative hagiography of a biblical figure which is more inclined towards an arthouse aesthetic than anything in the “faith-based” sub-genre. The beautiful score from Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson (Arrival) is wonderfully haunting and affective, the music perfectly complementing the stunning images of the Italian countryside serving as ancient Israel. Aesthetically, the film is simply marvelous to behold. Theologically, this portrait of the “apostle to the apostles” is one of the more interesting and complex iterations of biblical narratives I’ve seen in recent years. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray in UK)

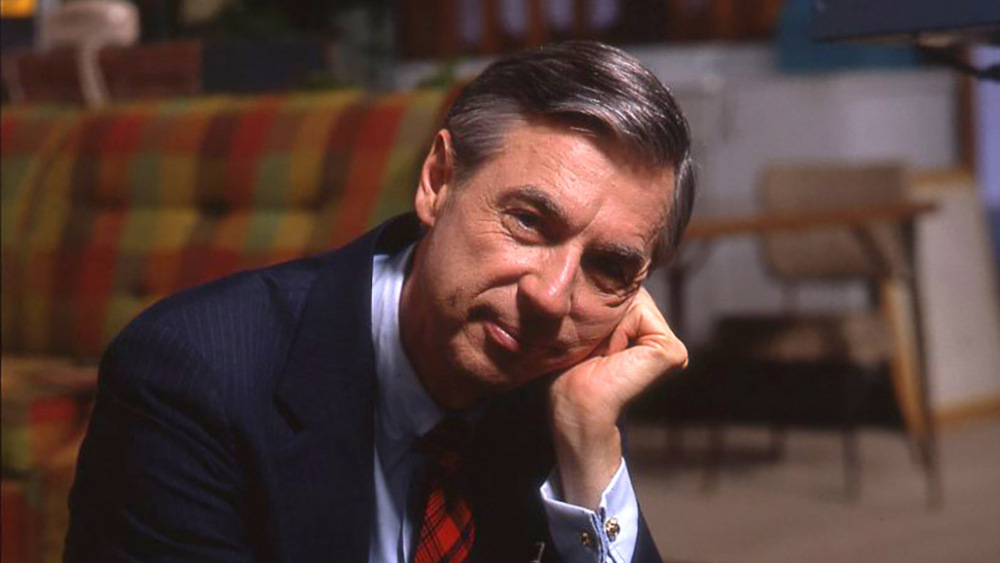

12) Won’t You Be My Neighbor? (Morgan Neville). The remarkable affectivity of Fred Rogers is not due to his wow-factor or stylish performance (Neville’s documentary isn’t particularly flashy either). What makes Rogers so incredible is his incarnation of unconditional love. This isn’t a shallow or sentimental love, but one which clearly emerged from Rogers’ theology. The various interviewers discuss this, that Rogers was living out his Christian theology and faith via television, trying to spread as much of Christ’s love as possible, all without resorting to overt religious language or proselytizing/apologetic methods. As Rogers says, “Love is at the root of everything–all learning, all parenting, all relationships. Love or the lack of it.” It turns out that genuine love is, in fact, good news. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

11) Monrovia, Indiana (Frederick Wiseman). Observational and comprehensive, Monrovia, Indiana is about as close as one can get to experiencing this middle-America community without simply going there. Wiseman’s camera moves about the community with a steady rhythm, the montage of images like a tour guide invited into every nook and cranny. What is striking is how Wiseman’s images feel deeply intimate without becoming invasive, revealing while still respecting the subjects–it’s a true “God’s eye view” via the silent presence of the camera.

10) You Were Never Really Here (Lynne Ramsay). Centering on psychologically-shattered military veteran Joe (Joaquin Phoenix), Lynne Ramsay’s thriller is tense and disconcerting, yet richly affecting, even tender. The sound design and disjointed montage create the perfect unsettling aesthetic for Joe’s fractured psyche, with jump cuts and sudden volume changes keeping the audience in a constant state of tension and dread. It’s a cinematic PTSD aesthetic, one bolstered by Phoenix’s fully-embodied performance and Ramsay’s keen directorial decisions. (Available on Amazon Prime US and UK)

9) Shoplifters (Hirokazu Koreeda). An artisan of empathy, Hirokazu Koreeda’s gorgeously-shot and perfectly-acted Palme d’Or-winning film Shoplifters fits well within his pantheon of masterpieces examining the definition of “family.” The rich mise-en-scene and powerful performances elevate Shoplifters from a sentimental melodrama to something much more complicated and affecting. Koreeda’s camera is patient and kind, giving gentle attention to particular places and things in this corner of the world.

8) Black Panther (Ryan Coogler). A cinematic black liberation theology and parable, Ryan Coogler’s contribution to the superhero genre is the best film in the MCU, and the film I re-watched most in 2018. The world-building of Wakanda is wondrous, the details of every costume and set rich and vibrant. There’s not a single underwritten persona; every single role is fleshed out, motivations are clear without becoming glaring, and not a minute of screen time is wasted. The internality of characters is revealed by both decisions and words, suggesting that perhaps it’s okay to both show and tell in cinema if done with care and direction. A deeply political film which transcends the arthouse/entertainment (false) dichotomy, Black Panther is simply marvelous. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

7) The Rider (Chloé Zhao). Richly empathetic and authentic, The Rider depicts the reality of life in this particular time and place without ever becoming expository. By using untrained actors essentially playing themselves, filmmaker Chloé Zhao allows us to get a true sense of what life is actually like on the dusty margins in the center of America. Tender and visually rich, Zhao’s contemporary nu-Western both affirms and subverts its generic roots, deconstructing and reconstructing the masculinity, violence, and individualism of the American myth. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

6) Madeline’s Madeline (Josephine Decker). Emotionally vibrant, aesthetically innovative, and charming as hell, Madeline’s Madeline is wondrous. Identity and metaphor blur together within Madeline’s Madeline‘s expressionistic story, a coming-of-age tale which takes personal subjectivity quite seriously. Josephine Decker imbues Madeline’s Madeline with a paradoxical authenticity and fantasy–characters and performances feeling strikingly real even as there is a sense of dreamy staged artifice about every moment. And newcomer Helena Howard gives the best performance of 2018 as Madeline. (Available on Amazon Prime US, Kanopy)

5) Roma (Alfonso Cuarón). Roma is a haunted house film where the ghosts are memories. Though less enigmatic and elliptical, Alfonso Cuarón’s film reminds me of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror via its cinematic exploration of traces in time and the lingering significance of a particular place. A formalist exercise with impressive black-and-white cinematography and slowly meandering pans and long-takes, Roma’s mise-en-scéne is so richly complex you’ll feel the need to pause the film just to take in the scenery. At-once nostalgic and fresh, Roma finds transcendence in the mundane moments of everyday lives and ordinary people–hanging laundry, staircases, car mirrors, airplanes overhead, soap bubbles. It is a beautiful celebration of peoplehood and place in an often place-less world. (Netflix, select theaters)

4) Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, and Rodney Rothman). The best surprise of 2018, and the only film I saw twice in the theatre, is an animated superhero film. Emerging from the brilliant minds of Phil Lord and Chris Miller, Spider-Verse is SO much without being TOO much. It’s a great animated film and a celebration of the medium of animation, pushing the boundaries of illustrations and CGI in ways that I think will genuinely transform the entire form. A great superhero film. A great comic book film. A great coming-of-age film. A great New York City film. A great comedy. A great action film. A great ensemble film. Even a great *Christmas* film. In short, it’s perfect. Go see it in a theater now. (In theaters)

3) Eighth Grade (Bo Burnham). Bo Burnham’s masterful directorial debut Eighth Grade is so authentic in its depiction of early adolescence that it should come with a trigger warning: this will be awkward, and could bring back those stuffed-down memories of middle school you’ve been trying to forget. Eighth Grade captures early adolescence with a raw honesty and realism rarely depicted or celebrated on screen. So many coming-of-age films either avoid or sensationalize the middle school years. Eighth Grade is destined to be included in the early adolescent cinematic pantheon alongside The 400 Blows, Kes, Welcome to the Dollhouse, and Moonrise Kingdom precisely because it simply presents middle school as it is, acne and all. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

2) Leave No Trace (Debra Granik). Leave No Trace is the very definition of a cinematic parable. A tale of a father and a daughter making their way through the world, the film is striking in its simplicity, yet its generates a genuine sense of awe via its profundity and beauty. There are no villains to be seen here; every character is genuinely good, and Debra Granik’s script and camera is careful to view everyone on screen with a sense of care and dignity. Every single person in Leave No Trace is seen and depicted as just that: a person, a human being, a significant Other. Like her earlier film, Winter’s Bone, Granik points out the beauty and brokenness within the margins of society, the quiet corners where we rarely glance yet are imbued with significance and truth. It’s also a Portland, OR film, a city dear to my heart. (Available on DVD/Blu-ray or streaming rental)

1) First Reformed (Paul Schrader). Here’s what I wrote for Think Christian about my favorite film of 2018: First Reformed is a masterpiece of spiritual cinema, a prophetic lament of theological, political, and personal significance. Alluding to Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson in both form and content, Schrader’s ascetic aesthetic—the minimalist gray-and-beige environments captured in static or slow-pan shots—is powerfully affecting as Ethan Hawke’s Reverend Toller navigates his personal dark night of the soul after a counseling session with a troubled young couple goes horribly awry. A cinematic theologia crucis at the intersection of hope and despair, First Reformed triggered a spiritual crisis in my own heart, one where I truly had to wrestle with its central question: Will God forgive us? Even as I know there is grace in Christ, I’m still wrestling with the query. Such is the lingering power of First Reformed, a film which dares to ask the tough questions of faith, inviting us not only to contemplate them but to do something about them. (Amazon Prime US, Kanopy)

Leave a Reply