In 2009, I posted a list of my top 10 horror films at my original blog. Ten years later, and my horror tastes have both deepened and expanded. In 2013, I posted a five-part theology of horror at my personal blog, much of which I still agree with, especially the contention that the most beautiful and truth-filled horror story is, paradoxically, found in the Gospel of Christ. A man is tortured, nailed to a wooden plank before a bloodthirsty mob, then rises from the dead (and so do others!). Salvation is found in his blood, even as he commands his followers to eat his flesh and drink his blood. Is this not horror? Yet it is also redemption.

For the 2019 Halloween season, here are my current Top 20 Horror Films, listed in alphabetical order:

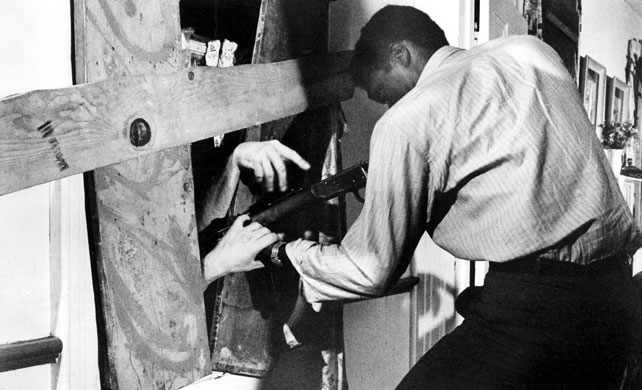

The Act of Killing (2012, Joshua Oppenheimer). This horrifying documentary is Oppenheimer’s in-depth and intimate look at the gangsters and killers who orchestrated a movement of government-sanctioned mass murders in Indonesia in the 1960s. The murderers are nonchalant and even proud of their violent deeds, and view themselves as local celebrities in their towns where they are still feared. Oppenheimer invited the killers to reenact their murders for the screen, to essentially make a movie about themselves, to which they happily agreed. Perhaps one of the strongest and most disturbing filmic real-life examinations of the depths of human depravity (and the tiny possibility for redemption). The horrors of Forgotten History.

Alien (1979, Ridley Scott). “The perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility … I admire its purity.” Ash’s description of the xenomorph is an apt description of Alien itself, a haunted house tale set in deep space, where…well…no one can hear you scream. Atmospheric, daring, and filled with verve, this is a film with a pulse. Weaver’s Ripley is one of the all-time greatest of film heroines, horror or otherwise. The horrors of Blue-Collar Labor.

The Babadook (2014, Jennifer Kent). Australian filmmaker Jennifer Kent uses atmosphere, sound, design, deliberate cinematography, and an affecting story to create one of the most compelling horror films I’ve experienced from this past decade. There isn’t much gore or violence, just a linger sense of dread and an unsettled feeling about the unknown nature of the Babadook. The design for Mr. Babadook is like a German expressionism vision of Jack the Ripper, and certainly a nod to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. How the Babadook became a queer icon is still a mystery to me. The horrors of Bad Children’s Storybooks.

The Birds (1963, Alfred Hitchcock). When I first saw this decades ago, it scared me because of the mysterious, frightening flocks of birds. Seeing it again now, it’s scary because of the mysterious, frightening masses of people. The entire phone booth sequence, including the two café scenes which serve as bookends, is an incredible blend of psychological intuition and cinematic prowess. I used to count this as a silly spectacle and minor Hitchcock, but I think I was mistaken. Those seagull squawks are perfectly awful. The horrors of Bad Café Patrons.

The Devils (1971, Ken Russell). This is essentially A Man for All Seasons but as expressionistic torture-porn. Based on the historical events of the rise and fall of Urbain Grandier, a 17th-century Roman Catholic priest executed for witchcraft following the Loudun possessions in France. Sometimes church history is just totally bonkers. Vanessa Redgrave gives an unsettling go-for-broke performance as a hunchbacked jealous nun. Violent, disturbing, and irreverent, there is nevertheless a contemporary relevance here—America’s current political/religious climate doesn’t feel too far removed from what’s depicted here as ideologies, political power, and sexual obsession become normative. Horrific indeed. The horrors of Horny Nuns.

Eraserhead (1977, David Lynch). This perfectly captures the maddening, mind-boggling horror of emerging adulthood and being a brand new parent. The kernel of everything Lynch has ever done since can be discerned here, a surreal nightmare featuring some the best sound design in cinema, and more WTF moments per minute than any other film I’ve ever seen. The horrors of Staying Up All Night With a Crying Baby.

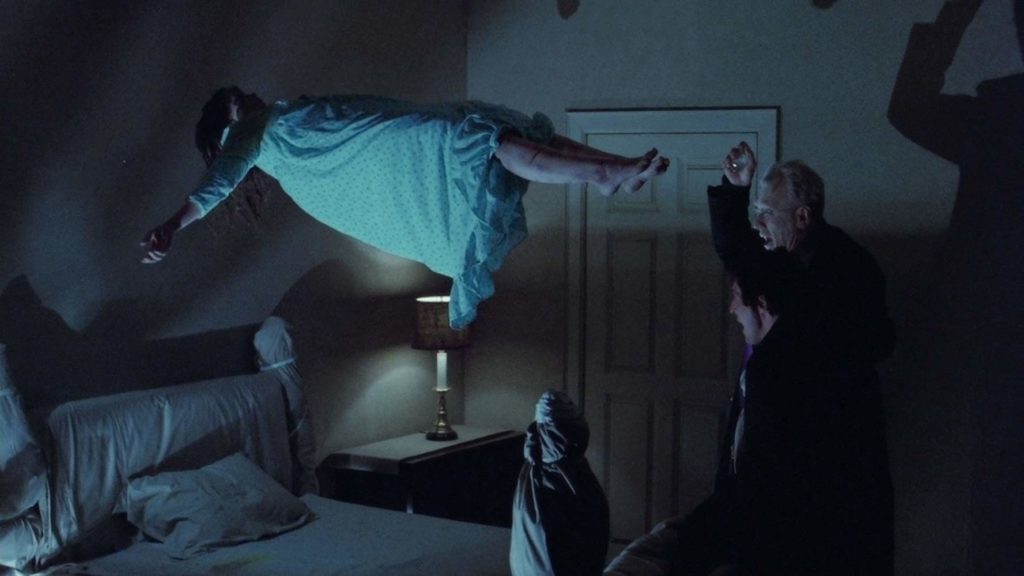

The Exorcist (1973, William Friedkin). One priest declaring “the power of Christ compels you!” while another priest sacrifices himself for the sake of the demon-possessed girl is about as Gospel-centric you can get with a horror film. Where science and psychology cannot save, Christ can and does. The horrors of Befriending Captain Howdy.

It Follows (2014, David Robert Mitchell). It does, doesn’t it? The image of the eyeless “giant man” entering the bedroom still haunts me. Sadly, the actor, Mike Lanier, passed away in 2018. The horrors of Post-Recession Detroit.

Jaws (1975, Steven Spielberg). Sometimes it’s hard to imagine Jaws as a horror film—it’s brightly lit, often humorous, and paced more like an adventure film. Yet the violence is gruesome and shocking, particularly the kinds of vulnerable victims Spielberg chooses (e.g. a young woman, a child). What’s worse, it’s the unsettling awareness that politicians are more interested in money and power than public safety, even in Small Town, USA. The horrors of When Your Boat is Not Big Enough.

Let the Right One In (2008, Tomas Alfredson). This non-Twilight teen vampire love story is a coming-of-age tale highlighting the horrors of early adolescence. The snowy grey setting and washed-out cinematography at times feels wonderfully and dreadfully akin to Kieslowski’s Dekalog. In the isolated world of Oskar and Eli, there are few adults who genuinely care for them (and those that do seem inept at their job). In this, Eli and Oskar fill the roles of both “friend” and “parent” in each other’s lives. They take care of each other, protect each other, provide for each other. Which is tragic. The horrors of Adults Who Don’t Stop Middle School Bullies.

The Night of the Hunter (1955, Charles Laughton). How does one classify this film? Is it a horror? A thriller? A film noir? A crime drama? A fairytale? A morality play? A Christmas movie? Whatever it is, it’s perfect. The horrors of Leaning On the Everlasting Arms.

Night of the Living Dead (1968, George Romero). I recently watched Romero’s Dawn of the Dead for the first time and found myself wishing I had simply rewatched the original. The low budget black-and-white aesthetic adds to its appeal, and the bold choices Romero makes—killing off Barbra, the racial undertones, Ben’s tragic ending—generates a timelessness to the film, even as it was very much of its time. The horrors of Rural Racist Cops.

The Phantom Carriage (1921, Victor Sjöström). In this silent Swedish classic, director Victor Sjöström plays David Holm, a drunken scalawag who neglects his family for his own hedonistic pleasures. On New Year’s Eve, he receives a visit from Death and ends up with the grim responsibility of the grim reaper himself. Part morality play, part horror-fantasy, the film is both formally distinct in its use of flashback and color, as well as wonderfully merciful in its denouement. The scene in The Shining of Jack hacking down the locked door has its origins in Holm. The horrors of Not Being Vaccinated for Tuberculosis.

Possession (1981, Andrzej Żuławski). It’s a toss-up as to whether Eraserhead or this film is the most disturbing and nightmarish film on this list. Depends on how you feel about cephalopods. Isabelle Adjani violently and passionately convulsing in a dank subterranean hallway is one of the most frightening images I’ve ever witnessed in cinema; Adjani deservedly won the Best Actress prize at Cannes for Possession and Quartet. And the scene is arguably not even the most outrageous and disturbing moment in the film. The horrors of Marital Infidelity.

Se7en (1995, David Fincher). Another film on this list which pushes the boundaries of horror vs. thriller, I’m convinced that Fincher’s film is more of the former than the latter. From the opening credits to the grisly murder scenes to John Doe’s apartment of insanity to the final “what’s in the box?” scene, there is an unsettling grungy dread which imbues every single frame. The horrors of Kevin Spacey Showing Up Uninvited.

The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick). I’ll share here what I wrote ten years ago: “What makes [The Shining] so scary and well-done is not only the art direction, editing, and cinematography—not to mention the incredible performance from Jack Nicholson—but the near-perfect analysis of evil and sin. Sin is both inner and outer, stemming from outside spiritual forces and inner selfish motives that drive people to evil and violent actions. Jack doesn’t enter the hotel a spotless and pure man. He has inner demons driving him to isolation; the outer evil simply awakens those demons further until he’s gone completely insane. Isolation from community perpetuates sin, removing accountability and the outside help that people need. We see this all the time when people harbor secrets, lead double-lives, or choose to embrace selfishness as a primary value for their lifestyle. The Shining simply shows us where sin ultimately leads us: death.” The horrors of Writer’s Block.

The Silence of the Lambs (1991, Jonathan Demme). Arguably the only horror film to win the Oscar for Best Picture (unless you count Hitchcock’s Rebecca from 1940), Demme’s direction and cinematography create a perfect sense of dread while also displaying a distinct care for every major player: Starling, Lector, even Buffalo Bill. Demme loves his movie’s characters, almost as much as Lector loves eating human beings. The horrors of Mispronouncing Chianti.

The Thing (1982, John Carpenter). If you found yourself trapped in Antarctica with a shape-shifting alien infecting and killing all your companions, what would you do? In Carpenter’s horror classic (a good argument for why movie reboots can be a positive practice), the thing is never fully explained, never totally revealed, never given a why for its rampage. It simply is, and it wants blood. And there’s lots of blood, and guts, and other body horror images too gruesome to describe. Like Alien before it, this features a stellar cast of characters with well-established distinct personalities—you care about every person, every death. Not for the faint of heart. The horrors of Opening Containers That Aren’t Yours To Open.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992, David Lynch). The second Lynch film on this list (I considered adding Mulholland Drive and INLAND EMPIRE as well, though those are arguably more neo-noir or thriller) is a psychological nightmarescape, at the center of which is Laura Palmer, an entity called BOB, and the Black Lodge. I’m late to Twin Peaks fandom, but Lynch’s bizarre world set in the Pacific Northwest (the stomping grounds of my childhood) is equal parts distressing and captivating. When I walked out of a theater screening of FWWM, I was disoriented and felt lost in reality itself. I didn’t know how to review or rate the film. I still don’t. The horrors of Systemic Family Abuse.

The Witch (2016, Robert Eggers). While I originally had Eggers’ The Lighthouse on this list, his debut film, The Witch, is such a finely-tuned, richly detailed, and spiritually disturbing film that I feel compelled to include it. An unsettling parable critiquing the American dream, The Witch is presented as a New England folktale as a strict religious Puritan family faces the devil himself. The horrors of Living Deliciously.

Caveat: Please practice personal discernment and caution regarding the above list—many horror films (like any genre) are not enriching or beneficial for every viewer, so use discretion and wisdom regarding your own viewing choices.

Leave a Reply