MPAA Rating: PG-13 | Rating: ★★★★

Release year: 2020

Genre: Documentary Director: Garrett Bradley

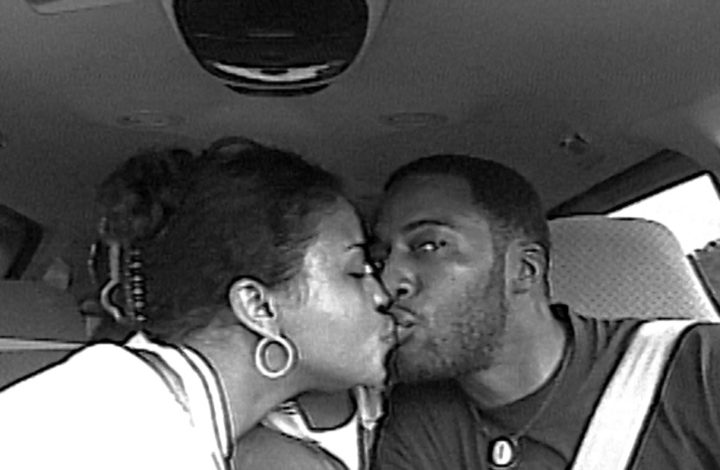

Garrett Bradley’s powerful and poetic documentary, Time, opens in medias res with intimate home footage from Sibil “Fox” Richardson. Part audio-visual epistle, part confession, the young woman speaks directly into the camera to her husband, Robert, who is serving a 60-year prison sentence for a bank robbery the young couple attempted in the early 1990s. While this premise for a documentary film suggests legal battles and emotional reunions—both of which are certainly present—the lyrical formal approach Bradley adopts with Time elevates an already-compelling story into the realms of transcendence. I don’t use that latter term flippantly; through its mysterious, even mystical montage of images and scenes, Time is a beautiful and evocative cinematic mosaic centered on the American (in)justice system.

Carefully and compassionately edited together by Gabriel Rhodes, the black-and-white imagery in Time washes over us like waves, telling Sibil’s story not through a straightforward narrative arc, but through an elliptical, often unnerving approach which requires audiences to truly pay attention. For many viewers, this unanchored approach may prove frustrating; Bradley forgoes title cards, talking head interviews, or introductions to the people on screen,, which can be quite confusing. In Time, we watch Robert and Sibil’s twin boys, Freedom and Justus, grow up from young boys into capable adult men; the couple have six sons Sibil has raised while Robert remained in prison. Yet it wasn’t until about mid-way through the film that I could figure out which son was which in the birth order; other family members and seemingly significant characters come and go without explanation. By the film’s conclusion, I was left with more questions than answers, more emotions and images in my memory than a clear understanding of what, exactly, happened. Poetry tends to do that.

Perhaps most significant in Time is the value of a spiritual community. We often see scenes in church worship services; in a particularly poignant and redemptive scene, Sibil apologizes to her congregation for her crimes and thanks them for supporting her and her boys. Humbling scenes like these are balanced by moments of the fiery Sibil preaching prophetic justice as a kind of modern-day abolitionist decrying the American mass-incarceration prison system and the number of Black men unjustly enslaved within it. Typically poised and prepared—Sibil, sadly, has learned how to “perform” for the mostly-white people she must politely put up with as she fights on behalf of her husband—we are given glimpses of her righteous anger which are as inspiring as they are intimidating. And I think this is indicative of Bradley’s underlying approach to filmmaking—Time is not as interested in providing us easy answers or a “happy” ending as much as it is meant to move us, provoke us, compel us, transform us. It as much about the redemptive power of cinema as memory-maker and audio-visual activism as it is about Sibil and Richard and their fight for freedom.

IMDB Listing: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11416746/

Leave a Reply