MPAA Rating: NR | Rating: ★★★★★

Release year: 1989

Genre: Drama, Foreign, Spiritual, Television Director: Krzysztof Kieslowski

Which of the Ten Commandments is your favorite? How would you rank them in order of preference? These questions, when applied to the ‘Ten Words’ at the heart of the Torah, appear unseemly or out of place. These divine injunctions are not meant to be categorized in order of preference—they are to be received in the order given by their author, and are most fully realized when viewed as a holistic framework rather than individual commands which can be parsed from their context. To rank the Ten Commandments is an exercise in missing the point. Perhaps the same could be said for ranking episodes in a film series.

The Decalogue—both the Judaic ethical principles passed down by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, as well as Krzysztof Kieslowski’s 10-episode film of the same name—is best understood as a whole, as well as a product of its cultural and historical context. Where the biblical Decalogue reveals the social ethics of a particular people, the ancient Jewish tribes, the cinematic Decalogue explores the social ethics of 1980s Poland under Soviet rule. These ethics are holistic in nature, the individual commandments and virtues overlapping and blending together in an ethical framework. William Jaworski notes the following: “The ten episodes display how the Commandments are best understood not as rules along the lines proposed by modern moral theories, but as descriptions of patterns of thought, feeling, and action that can influence human well-being for better or for worse.”[1] The Decalogue should be understood as a holistic reflection upon human nature and existence, emphasizing both the inherently depraved and broken aspects of humanity, as well as the glimpse of human goodness and hope. It is also a reflection not only of the community’s ethics, but the author’s view and interpretation of that particular community. The author, or auteur, of the film(s) is the director, Kieslowski; the author of the Hebrew Commandments is the divine.

While each Decalogue episode can be understood as thematically corresponding to a specific biblical commandment, both Kieslowski and the scriptural text are ambiguous enough to allow for a variety of nuanced interpretations. The very ordering of the Ten Commandments is interpreted differently between Jews and Christians, not to mention Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant distinctions. As Poland is primarily Catholic, the Catholic ordering is most likely for Kieslowski’s film(s). Yet interpreting the filmic narratives through the lens of a particular Commandment elicits different results, depending on the Commandment one assumes. For example, should Decalogue Three, a story about a woman interrupting her ex-lover’s Christmas celebrations to go on a fabricated search for her husband, refer to the commandment “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy”—the Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran numbering—or to the commandment “You shall not take the Lord’s name in vain”—the Jewish, Eastern Orthodox, and Reformed Church’s numbering? The film may be exploring human responses to the Lord’s Day or the Lord’s Name; in both cases, the filmic narrative has its own unique contributions beyond the scriptural text. Beyond the numbering, each of Kieslowski’s episodes incorporates more than one Commandment. The Commandment addressing adultery (either the Sixth or Seventh) can be seen in half of the films—Decalogue Two, Three, Four, Six, and Nine all have characters engaged in some form of sexual transgression against a partner or spouse. To see the whole biblical Decalogue, one has to view the whole filmic Decalogue.

The Decalogue emerged from a conversation between Kieslowski and his co-writer, Krzysztof Piesiewicz. “’Someone should make a film about the Ten Commandments,’ Piesiewwicz said to me. ‘You should do it.’ A terrible idea, of course,” reflects Kieslowski in his autobiography.[2] Originally, he intended to simply write the screenplays of the serialized cycle. “So I thought that if we wrote ten screenplays and presented them as Decalogue, ten young directors would be able to make their first film.”[3] Later, as the stories coalesced and the project emerged, Kieslowski realized his desire to direct, not just one but all ten of the films. He writes about his motivations and understanding of the film(s):

Decalogue is an attempt to narrate ten stories about ten or twenty individuals who—caught in a struggle precisely because of these and not other circumstances, circumstances which are fictitious but which could occur in every life—suddenly realize that they’re going round and round in circles, that they’re not achieving what they want.[4]

These individual lives and individual Commandments are unified as a whole by the enormous apartment complex where each character lives. “We wanted to begin each film in a way which suggested that the main character had been picked by the camera as if at random. We thought of a huge stadium in which, from among the hundred thousand faces, we’d focus on one in particular.”[5] The original idea was for the camera to seemingly pick a character out of a crowd and follow them, revealing their story and interior desires over the course of the film. In the final result, the huge apartment estate, with its homogenous concrete architecture and windows, serves as the perfect environment for Kieslowski’s vision. All of the characters live in this estate, yet all are separated as individuals; they live in immediate proximity of each other, yet remain disconnected. Kieslowski’s camera focuses on the interiors of the characters, their feelings and desires, as well as their living spaces. This interior emphasis is a subtle political statement in Communist-era Poland. Ewa Badowska notes this political subtext of The Decalogue and its filmic environment:

It is entirely plausible to read the overly intense atmosphere of the apartment buildings where the series takes place—the concentration, as it were, of inner drama within the walls of these residences—as a realist portrayal of the heightened significance of the private life under communism. Communism…was a social system in which the private itself was made perverse by the meaninglessness of the social and the system’s intentional devaluation and destruction of privacy.[6]

While he argues that he didn’t want to make a political film about Poland, Kieslowski’s approach nevertheless reveals this private/public dichotomy of the Communist social sphere, where people “have two faces. They wear one face in the street, at work, in the cinema, in the bus or car.”[7] Privacy is a privilege, and Polish audiences would have noticed this interior emphasis. In The Decalogue, Kieslowski’s camera intrudes upon the private lives of individuals in order to reveal the universal nature and struggle of human existence. Watching these films in contemporary 21st-century America, they nonetheless feel relevant and affecting as they address universal questions about morality, love, truth, and God.

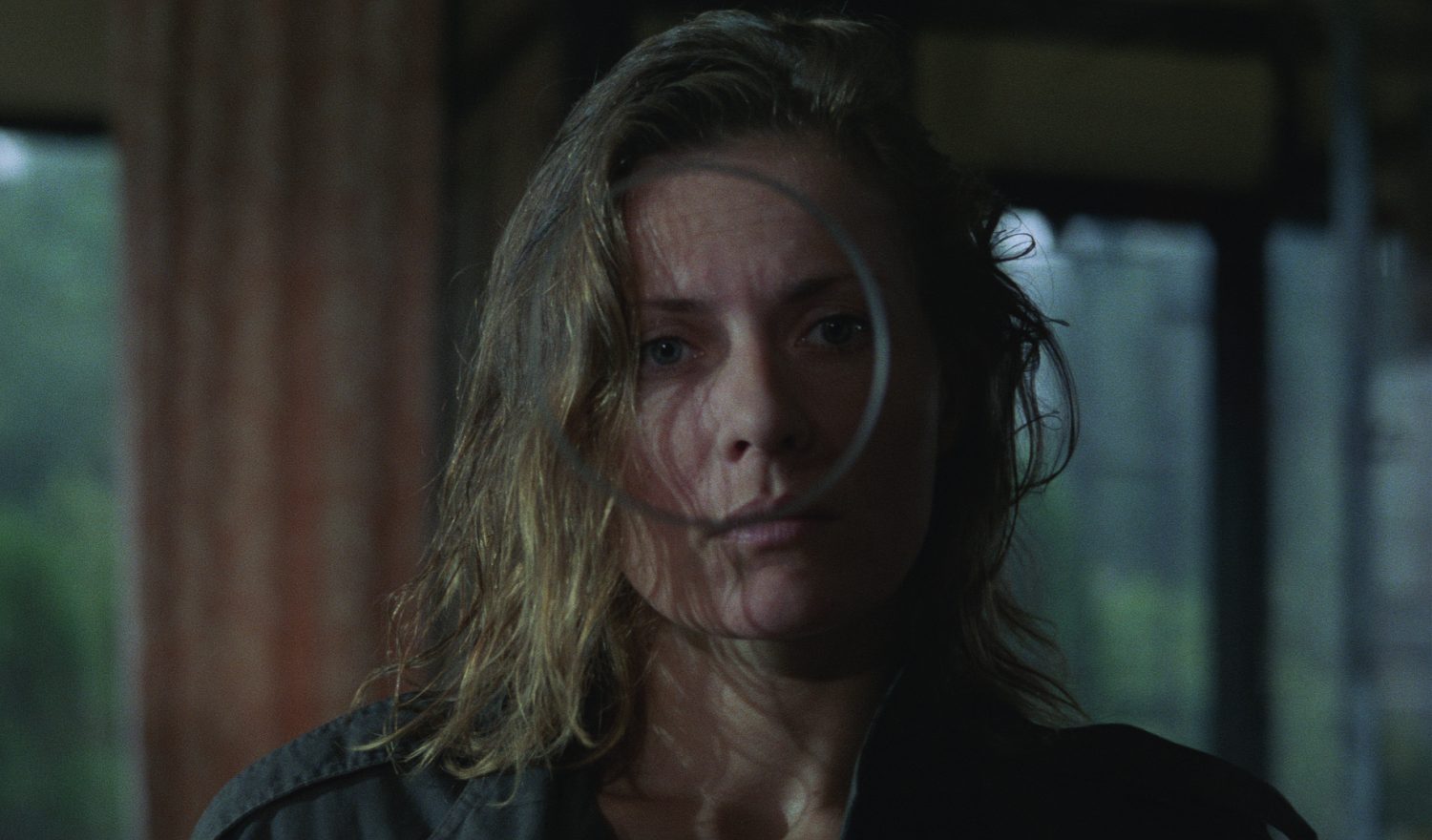

The presence of God can be seen in the silent witness, portrayed by actor Artur Barciś, who observes the main characters but never speaks or intervenes in any of their circumstances. Decalogue One opens with a shot of the snowy apartment complex and the frozen lake (which plays a significant role in the story’s outcome) before settling on the image of what appears to be a homeless man warming himself by the fire. The camera zooms in as the man scans the horizon before he stares directly into the camera, forcing the audience to gaze directly into the melancholic look in his piercing blue eyes (see the image below). This unnamed character appears at critical moments in all but two of the episodes—Seven and Ten—as someone who simply watches. The other characters never openly address him even when they do notice his presence. Michael Baur suggests that the regular appearance of this silent witness “serves to convey the important message that there may indeed be an overriding (theological) purpose at work in our fallen and alienated world.”[8] Yet his aloof expression and constant silence also suggest that this presence of the divine follows the theological tradition of deus absconditus, “the God who hides,” particularly in moments of human suffering or ethical dilemmas.

The Decalogue allows the viewer an empathetic glimpse into the particular context of Communist Poland in the late 1980s while also addressing wide-ranging ethical questions of incredible intimacy. These filmic stories are weighty and uneasy to observe, the ethical topics complex and provocative. In Decalogue Eight, in a meta-commentary on the film(s), an ethics professor guides a classroom conversation about the dilemma raised in Decalogue Two, a question of whether or not a woman should have an abortion. It’s as if Kieslowski is inviting audience participation—these are not films to simply watch for entertainment (though they are certainly well-crafted and never boring), but films to discuss, which should bring about further ethical inquiry and theological enrichment. Kieslowski once stated, “If I had to formulate the message of my Decalogue, I’d say, ‘Live carefully, with your eyes open, and try not to cause pain.’”[9] Just as the transcendent witness watches human interactions with eyes wide open, and just as Kieslowski’s camera peers into the lives of individual characters with intimate care, so The Decalogue prompts the viewer to observe their own world, both interior and exterior, with renewed ethical vision.

—

[1] William Jaworski, “Rules and Virtues: The Moral Insight of The Decalogue,” in Of Elephants and Toothaches: Ethics, Politics, and Religion in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalogue, ed. Eva Badowska and Francesca Parmeggiani (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), 15-16.

[2] Krzysztof Kieslowski, Kieslowski on Kieslowski, ed. Danusia Stok (London: Faber and Faber, 1993), 143.

[3] Kieslowski, 144.

[4] Kieslowski, 145.

[5] Kieslowski, 146.

[6] Badowska, 154.

[7] Kieslowski, 146.

[8] Badowska, 136.

[9] Annette Insdorf, Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski (New York: Miramax Books, 1999), 124.

IMDB Listing: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0092337/

Leave a Reply