What left is there to say about the year that was 2020? To call it “unusual” or “difficult” underplays the immense trials and tragedies the entire global population faced. Cinema itself was not left unscathed; as productions halted, theaters closed, festivals went virtual, and distributors scrambled, the film industry was totally upended. Likewise, film audiences (i.e., human beings) were isolated to their homes in quarantines or lockdowns (at best—we know the worst of what Covid-19 can do) and attempted to pass the time via the various streaming services which now reign within the film industry. We may not have gone to the movies in 2020, yet the audio-visual form has become the global lingua franca; through the cinematic technological apparatus of videos and screens, we’ve attended school and church, weddings and funerals, and remained in contact with loved ones from across the world. These contemporary realities mean the very definition of “cinema” is shifting, and the films on my top 20 list reflect this transformation: many of these movies never had a wide theatrical release and premiered only on streaming platforms; two are filmed Broadway performances, and one is a “TV movie” in a five-part anthology. André Bazin’s query of “what is cinema?” 70 years ago continues to carry relevance.

The last film I saw in theaters was Pixar’s Onward in February; my only other theatrical experience of 2020 was a special screening of A Hidden Life I hosted in St Andrews that same month. And yet I have managed to watch over 360 films in 2020, or around one film per day. I also read 47 books, published three academic journal articles and three academic book reviews, wrote a dozen articles for popular online publications, and finished the complete draft of my PhD thesis on theology, philosophy, and the films of the Dardenne brothers. For me, it’s been a very difficult year, and yet also a productive one. Here’s hoping that 2021 brings renewed hope, peace, and healing.

Here are 20 of the films that helped me endure 2020. These are the “favorites” and “bests” that were available to me this past year. If a film doesn’t appear, it means (a) I didn’t see it, or (b) I didn’t like it as much as these 20 films when I wrote this list. If you disagree with my choices or rankings, that’s fine; please feel free to launch your own website and make your own list. Ultimately, I merely hope to point you to the true, the good, and the beautiful in cinema from 2020.

20. Promising Young Woman (Emerald Fennell). Carey Mulligan gives a career-best performance in this darkly comic exploitation/thriller film from writer-director Emerald Fennell. It’s an emotional rollercoaster of a tale, swinging from wildly funny to deadly serious, sometimes in the same scene. This film does not care what you think about it; it just wants you to wake up and pay attention to the injustices women face in our culture, as well as confront those who enable men to get away with such injustices.

19. The Personal History of David Copperfield (Armando Iannucci). Sometimes you watch a film and it speaks into your situation for that week/day/hour, as if it were a providential messenger of hope. This is precisely what happened when I watched Armando Iannucci’s delightfully madcap adaptation of Dickens’ classic book. On a particularly depressing day when it felt like everything I work for and value—the arts and humanities, religion and theology, youth ministry and education, social justice—wasn’t making a bit of difference in the world, I watched this film and it renewed a sense of purpose in me. Dev Patel has never been better, and the supporting performances from Tilda Swinton, Peter Capaldi, and Hugh Laurie are brilliantly funny.

18. Bull (Annie Silverstein). I saw this underrated gem in 2019 at Cannes, and it feels like it was unjustly ignored, swallowed up in the lack of distribution and marketing in 2020. Annie Silverstein’s first feature film is a tender neo-Western drama which draws apt comparisons to films like Debra Granik’s Winter’s Bone, Andrew Haigh’s Lean on Pete, and Chloé Zhao’s The Rider. Rob Morgan gives a phenomenal performance as Abe, an aging bullfighter clown in the Texas rodeo circuit who encounters a rebellious young teen girl (newcomer Amber Havard) and forms an unexpected mentorship. Seek this film out.

17. Another Round (Thomas Vinterberg). The premise for Danish filmmaker Thomas Vinterberg’s latest collaboration with Mads Mikkelsen hints at the film’s hilarity: based on the ideas of an obscure philosopher, four middle-aged high school teachers launch an experiment of maintaining a constant low level of intoxication. Hijinks and tragedy ensue. But what sounds like a Judd Apatow script is imbued with pathos and complexity under Vinterberg’s capable direction, and Mikkelsen’s performance is strikingly affecting and invigorating. This opens with a Kierkegaard quote and concludes with one of the strongest final scenes from any film in 2020.

16. The Painter and the Thief (Benjamin Ree). When two paintings are stolen from a gallery in Oslo, it sparks a very unusual friendship between the artist, Barbora Kysilkova, and one of the thieves, Karl-Bertil Nordland, when she asks to paint his portrait. A composition of both ethics and aesthetics which reveals the beauty of repentance, Ree’s carefully constructed documentary plays out like a psychological thriller mixed with a romantic drama, yet unfolding with real individuals over the course of three years. One can readily imagine the American-made adaptation starring Claire Danes and Alexander Skarsgård. If I ever write a book on film and ethics, this doc would be included.

15. David Byrne’s American Utopia (Spike Lee). While Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods is arguably the stronger and more bombastic film overall, this documentary of Talking Heads’ frontman David Byrne’s Broadway show is like a glimpse of heaven, where every tribe, tongue, and nation comes together to sing in rhythmic praise and joy. It’s a percussionist’s paradise which demonstrates a perfect rhythm between effervescent joy and no-nonsense political urgency. As both a film critic and a drummer, I absolutely loved it. And as I watched Stop Making Sense for the first time in 2020, this was a great “sequel” to that perfect concert film from 1984.

14. What the Constitution Means to Me (Marielle Heller). This may be the most surprising and underrated film on my list. Like American Utopia, this is a filmed version of a Broadway production, that of Heidi Schreck’s one-woman show which presents both her personal experiences with the U.S. Constitution, as well as a critical historical overview of various laws and norms for women in America. Schreck’s writing and performance is erudite, entertaining, and remarkably vulnerable, but it’s also Marielle Heller’s stellar direction which elevates this from being merely a recorded theatrical production into the realm of compelling and prophetic cinematic art.

13. Wolfwalkers (Tomm Moore, Ross Stewart). The latest Irish folklore animated film from Cartoon Saloon features a brazenly hand-drawn aesthetic; in a world where CGI reigns, it’s refreshing to see such a classic look. The film centers on an unlikely friendship between English apprentice hunter Robyn and the Irish wolfwalker Mebh. The plot elicits comparisons to both Pixar’s Brave and director Tomm Moore’s earlier film The Secret of Kells, yet it contains a distinct combination of political critique of English-Irish history, as well as an appreciation of Irish mythology and the more enchanted world of bygone eras.

12. Palm Springs (Max Barbakow). In a year where nearly everyone felt “stuck” at some point, Palm Springs is a comedy oasis in the desert. Building upon a Groundhog Day-like premise and taking it into new existential territory, the story centers on Nyles (Andy Samberg) and Sarah (Cristin Milioti), who find themselves stuck together in an infinite time loop while attending a wedding in the titular California desert paradise. In some ways, the film is a Millennial throwback to the “comedies of remarriage” of classic Hollywood in that it relies on witty banter between our two love interests, as well as landing on a remarkably traditional affirmation of marriage.

11. Minari (Lee Isaac Chung). This poignant, earnest film about a Korean family’s highs and lows in Reagan-era America is a strikingly honest tale portraying the immigrant experience, particularly from an Asian-American perspective. As Jacob (Steven Yeun) and Monica (Han Ye-ri) strive to make a better life for their two young children, David (Alan Kim) and Anne (Noel Kate Cho), on a patch of rural land in Arkansas with the help of Monica’s foul-mouthed mother (Youn Yuh-jung), it generates tensions between the couple which threaten to break the family apart. The depiction of religion in Minari is noteworthy, in that it’s very overt while also being quite subtle; the film neither downplays nor idolizes faith (in God, in money, in family, in one’s own intellectual faculties and hard work) but rather simply shows it, and shows it simply. The film will open wider in February 2021 in the US and March 2021 in the UK.

10. Tenet (Christopher Nolan). I strongly disagreed with Nolan’s insistence on Tenet opening in theaters in the midst of a global pandemic, and I still do; indeed, I think watching the film from the safety of my own home was the better cinematic experience. Though I can appreciate the various valid critiques of Christopher Nolan films—too long, too loud, too masculine, too incomprehensible—I also found Tenet to be a remarkably thrilling take on the James Bond franchise, as well as Nolan’s most overtly philosophical and theological film to-date. Even as the film operates like a video game, moving its Protagonist (a charming John David Washington) from level to level, set piece to set piece, it also raises questions about the relationship between time and ethics, as well as the ethics and politics of technology itself.

9. Time (Garrett Bradley). It feels cliche to call Garrett Bradley’s hauntingly affecting documentary “poetic,” but the montage of home footage from Sibil “Fox” Richardson interspersed with Bradley’s own captured images of Fox’s quest to gain freedom for her imprisoned husband, Robert, is certainly poetical. Time is not as interested in providing us easy answers or a “happy” ending as much as it is meant to move us, provoke us, compel us, transform us. It as much about the redemptive power of cinema as memory-maker and audio-visual activism as it is about Sibil and Richard and their fight for justice, to simply be together as a family.

8. Shithouse (Cooper Raiff). If you dismiss this film based on its offensive title, you may miss out on this deeply affecting and profound portrayal of late adolescence which pays tribute to the coming-of-age tradition even as it forges new emotional pathways. Twenty-three-year-old Cooper Raiff wrote, directed, edited, and stars in his feature-length filmmaking debut about a college freshman, Alex (Raiff), and an encounter with his sophomore R.A., Maggie (Dylan Gelula). The comedy is fresh, the dialogue rings true, and the story itself is deeply affirming of honesty and authenticity in relationships.

7. Lovers Rock (Steve McQueen). Steve McQueen’s “Small Axe” anthology series of five films depicting the lives of Caribbean individuals living in London in 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Film critic Josh Larsen compared the films to Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog, stating “Small Axe…shares Decalogue‘s scope, moral conviction, and awesome artistry. It’s intimate yet expansive, episodic yet cinematic.” The second film, Lovers Rock, is the pinnacle of the series. It’s a romantic work of corporeal and spiritual liberation, breaking free from the conventional bounds of narrative story-telling in order to simply be its beautiful joyful self. The film centers on a reggae house party in 1980s West London, and…that’s it. Sure, conflicts happen; characters grow; love blossoms. But Lovers Rock is more interested in dancing in the moment than moving on to the next plot point. In the Gospels, the kingdom of heaven is often compared to a banquet or party. Enjoy it.

6. The Climb (Michael Angelo Covino). I saw this terrific comedy at Cannes in 2019, and it’s the first film which ever used a pull quote from my review in the movie’s poster and trailer. Though The Climb is a comedy, it’s incredibly serious about cinematography and mise-en-scène; the film is structured as seven vignettes, with each chapter often shown in a single long take, often using framing and blocking to support the witty comic dialogue. The Climb is a bromance between Mike (Covino) and Kyle (Kyle Marvin, co-writer and real-life BFF of Covino) which addresses toxic relationships and the value of true friendship.

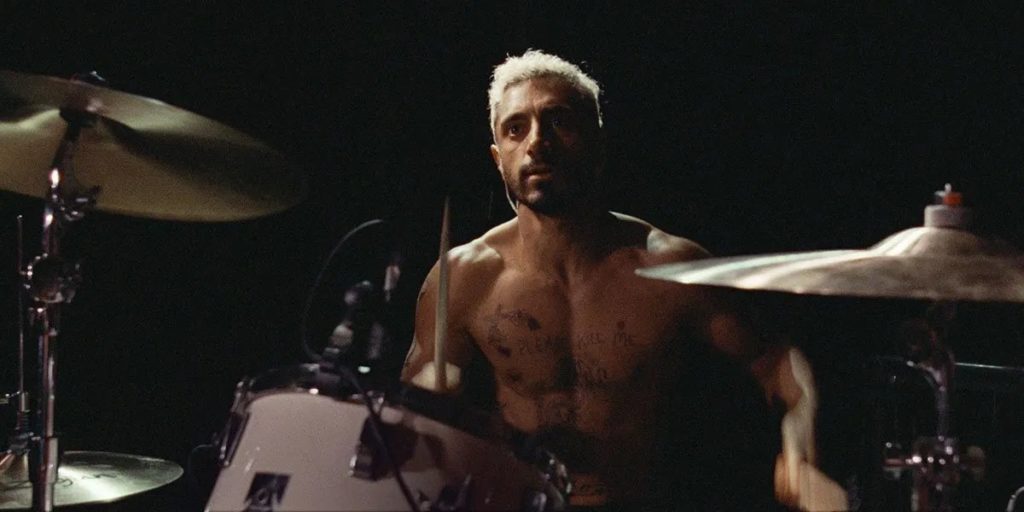

5. Sound of Metal (Darius Marder). Writer/director Darius Marder’s debut feature-length film demonstrates precisely how cinema is an audio-visual form as it empathetically allows us into the experience of Ruben (Riz Ahmed), a heavy metal drummer who suddenly experiences hearing loss. The film often places us in Ruben’s head, allowing us to hear (or not hear) what he’s hearing, creating a sympathetic sonic landscape which left me more attune to the world around me. Both the script and the performances consistently surprised me with their creative and compassionate decisions, always taking the harder-but-better path towards subtlety and restraint while never feeling repressed. Ahmed’s portrayal of Ruben is my favorite performance of 2020, and the final shot is about as perfect of an ending as you can get.

4. First Cow (Kelly Reichardt). I love Kelly Reichardt’s visions of the Pacific Northwest as a simultaneously harsh and humane environment which shapes its inhabitants for a life of resilience. This patient, tender neo-Western tale of friendship in 1800s Oregon also serves as a parable critiquing the American myth of financial freedom and capitalist ideology (not unlike my #2 film). The performances from John Magaro and Orion Lee as Cookie and King-Lu, respectively, are so unassuming and natural; there’s a comfort to their interactions, like a well-worn leather glove. The film features some of the best cinematography of the year, capturing the sunlight and colors of the autumnal Oregon landscape. And I must admit, the eponymous cow is absolutely gorgeous.

3. Young Ahmed (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne). My appreciation of the Dardennes’ most controversial film has only increased upon each revisit. It explores volatile issues, particularly cultural conflicts of interpretation at the boundaries of secular and religious ideologies, through the Dardenne brothers’ signature lens of empathy and compassion. It offers no easy answers or resolutions; parables rarely do. Instead, it provokes us to make our own interpretations and ask: is it possible to sympathize with—even forgive—individuals who have become entrenched in dangerous religious or political ideologies, especially if they are repentant? What can or should be done to help de-radicalize people caught in such paradigms? Let the reader understand.

2. Nomadland (Chloé Zhao). Nomadland is an achingly moving work of transcendent cinematic art which is, paradoxically, humble and confident, fanciful and true. Zhao’s masterpiece presents the nomadic van-dwellers living in the American West in the post-Great Recession era, with Fern (Frances McDormand, in one of her best performances) as our guide. It’s a decidedly Malickian film, and the cinematography is the best of the year. Certain images stand out in my mind: a sunset, a door frame, a rocky landscape, a dinosaur statue, a flowing river—all are imbued with a kind of spiritual energy or vibrancy, even a wisdom. With Nomadland, Zhao proves that she’s one of the most outstanding contemporary working filmmakers.

1. Dick Johnson Is Dead (Kirsten Johnson). Part memoir, part memento mori, filmmaker Kirsten Johnson’s cinematic project strikes a perfect balance between hilarity and poignancy, between the fantastical and the all-too-real. No other cinematic experience from 2020 moved me as much as this, which at times left me laughing until my sides hurt, as well as crying until I was a sniffling wreck. As Kirsten faces the inevitable death of her beloved father, Dick, the cinematic medium becomes a mode for grieving and remembering, honoring and healing. Through the afterlife sequences, the film also has a distinctly eschatological theme; indeed, it is an overtly theological work of art. In a year which was uniquely marked by the tragedy of death due to Covid-19, Dick Johnson Is Dead serves as a cinematic funeral and an invitation to celebrate life to the fullest while we still have breath within us. May we weep with those who weep, but also laugh with those who laugh, enjoying every single moment we can with those we love.

Honorable Mentions: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (George C. Wolfe); I Am Greta (Nathan Grossman); The Vast of Night (Andrew Patterson); Yes, God, Yes (Karen Maine); Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles).

I watched Tenet last night based off of your recommendation. I am still trying to wrap my head around it, but thanks for your insight. It is an interesting story and alludes to the fact that if we know the big picture of life, it makes sense about why things may happen. But, if we focus on the now and temporal, the larger picture is lost and can cause carnage and also lasting damage.

Thanks for your insight, Joel! I think you comment hints at the potential eschatological dimensions of “Tenet”, how a future-oriented posture informs our behaviours in the present, even if the future presented in the film is more hostile than hopeful.