In 2015, I published a Top 10 of the 2010s So Far. While my top 2 films haven’t changed—they’re my two all-time favorite films—the past decade has given us a smorgasbord of cinematic treasures. This list began as a top 10, then expanded to a top 20, then a top 25, then a top 50…then I added 17 more. And I still feel like I’ve left out some wonderful films. Truth, goodness, and beauty are expansive like that.

Here is my list-making methodology:

- The decade is here defined as 2010-2019. Some will say the decade is 2011-2020. These people are like the kid at the sleepover who, when everyone says goodnight, yells, “Actually, it’s ‘good morning’ cuz it’s past midnight!”

- I’ve limited films to two (2) per director. Otherwise, all of the Dardenne brothers’ movies from this decade would be here.

- If a film isn’t here, it’s because I haven’t seen it or didn’t love it as much as these films when I wrote the list. Or I forgot.

- I’ve included links to reviews or essays I’ve written, where applicable.

- This is how I’d rank these today, but if I published this list again, it’d probably be different. Don’t pay as much attention to the ranking as the films themselves. However, the top 10 are my official “Top 10” for the 2010s.

Please do share your own favorite films from the 2010s in the comments. May the 2020s offer us as many or more cinematic treasures to cherish.

67. Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017, Rian Johnson). Haters gonna hate, but The Last Jedi is the best Star Wars film since The Empire Strikes Back. Johnson’s divisive film was an experiment of expectancy. It pushed the boundaries of its characters, its audience, and the franchise’s capacity, upending our expectations even as it fulfilled ones we never knew we had. There are new worlds, new characters, and important new questions both raised and answered. To put it simply, this is a hopeful film; it is moving into the future of Star Wars even as it honors the past.

66. Something, Anything (2014, Paul Harrill). With an opening Christina Rosetti poem emphasizing the power of invisible spiritual forces in our world, Something, Anything sets the contemplative tone for its narrative, a story of personal loss and the journey toward healing and wholeness. While she doesn’t say much in the opening scenes, we can tell that Peggy (Ashley Shelton) is, by all accounts, successful. The scenes flash before us as snapshots of her wonderful life—a marriage proposal from a handsome man in a trendy setting; a beautiful wedding surrounded by friends; the enormous and well-decorated house in the hills of Knoxville, Tennessee; the joyful news of a pregnancy. Harrill chooses to tell Peggy’s story in near-silence, and she rarely speaks throughout the film. Quiet piano music accompanies the beautiful, intimate cinematography, eliciting comparisons to Kieslowski’s Three Colors: Blue in its affecting and melancholy portrayal of a woman walking through a season of grief.

65. Phoenix (2014, Christian Petzold). Each of the main characters in Phoenix are elaborate, complex, and mesmerizing, and I found myself captivated by its taut script, powerful cinematography, and wonderful use of music and silence to communicate its ideas and stir one’s emotions. Phoenix stirs up a longing for the truth to be told, for confessions to be made, and for either reconciliation or retribution to be enacted. Christian Petzold draws a strong parallel with Hitchcock’s Vertigo without become a lesser copy of its predecessor; Phoenix is its own film, and stands on its own merits, and the direct allusions to Vertigo are in its favor.

64. Moneyball (2011, Bennett Miller). In my original review, I considered this film as a sort of leadership parable. Now, eight years later, it still holds up as one of Brad Pitt’s most understated and affecting performances. It also happens to be one of my favorite films about baseball, probably because it’s less about baseball and more about human relational dynamics and the importance of good research.

63. Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012, Benh Zeitlin). I have no idea where Zeitlin has gone after this remarkable debut, but I hope he’s up to something good. Filmed in the grainy and shaky realism of handheld cameras, this magical film felt like a poetically quirky combination of early David Gordon Green mixed with the fantastic animated worlds of Hayao Miyazaki.

62. Madeline’s Madeline (2018, Josephine Decker). Identity and metaphor blur together within Madeline’s Madeline‘s expressionistic story, a coming-of-age tale which takes personal subjectivity quite seriously. What is Madeline’s Madeline about? Mental health, adolescence, gender, parenthood, sexuality, the artistic and creative process, cinema, everything. It is a true metaphor, and per philosopher Paul Ricoeur, all true metaphors hold potentially infinite interpretations. At the center of it all is the titular teenage Madeline, played by newcomer Helena Howard, who gave the best filmic performance of 2018.

61. Wonder Woman (2017, Patty Jenkins). Wonder Woman is wonderful. I watched Wonder Woman three times in theaters, more than any other film from 2017. Patty Jenkins and Gal Gadot crafted something beautifully unique with this film: a nuanced message of hope and mercy in a violent world; a superhero motivated by love and a desire for peace; and a visionary portrayal of femininity in all its beauty, complexity, and strength.

60. It Follows (2015, David Robert Mitchell). More than any other horror film from this decade, Mitchell’s has lingered in my mind, following me with a relentless persistency. The “it” of It Follows is, at once, the consequences from our sexual actions, the lingering wounds of our past, and the impending certainty of death. Mitchell crafted a new horror classic, one which takes a simple idea and builds upon it with remarkable craftsmanship and ambition. Its original ideas and haunting images remain in your mind, trailing you at a persistent pace, unable to leave you alone as you contemplate what follows.

59. Take Shelter (2011, Jeff Nichols). A sort of Noah story, Michael Shannon’s performance as Curtis is the driving force behind Take Shelter. Director Jeff Nichols–who also directed Shannon in Nichols’ first film, Shotgun Stories–slowly builds a growing sense of fear through Shannon, who becomes a conduit for the mounting dread that permeates the film. Curtis is quiet and surprisingly normal, with brief explosive outbursts that allow for cathartic releases of tension while also cultivating more of it. A frightening and prophetic film.

58. Paddington 2 (2017, Paul King). I think I underrated this when it first was released. Imagine the spirit of Amelie Poulain, the quirkiness of a Wes Anderson film, and the humor of Monsieur Hulot or Charlie Chaplin, all set in jolly ol’ England. Moreover, the Paddington films are political films in the best sense of the word—they are about the people of society, how we ought to live our public lives and treat our neighbors, even if that neighbor is a bear sporting a duffel coat.

57. The Lost City of Z (2017, James Gray). In the lush and languid The Lost City of Z, director and screenwriter James Gray chooses a hazy, shadowy lighting and color palette, with warm tones and soft edges, imbuing a fantastic naturalism within every image. An epic, classical adventure, there is something dream-like about the whole narrative, as if it was conjured up in the imagination and memory of the characters themselves. The green-and-gold visual aesthetic alludes to both the sepia tones of bygone photography and the sweltering humidity of the Amazonian rainforest.

56. Moonlight (2016, Barry Jenkins). Moonlight is holistically beautiful. Its cinematography, its performances, its narrative, its ideas, its moments–there is an aura of empathy and glory surrounding all of it. Perhaps most visually striking is the lighting—everything in the film, particularly human skin and eyes, are aglow with allure and mystery. One of the few times where the Academy Award for Best Picture was absolutely right that year.

55. Spotlight (2015, Tom McCarthy). Where a lesser film might have sensationalized the events or manipulated viewers’ emotions with sweeping musical scores or Actors Who Emote, Spotlight relies on the power of the truth itself to foster both empathy and affection. The patience expressed in Spotlight is a long-lost discipline we need to recover in order to promote long-term justice. The truth can purify us, if we’d only give it time.

54. Black Panther (2018, Ryan Coogler). Wakanda forever.

53. Shoplifters (2018, Hirokazu Koreeda). Like many of Koreeda’s recent films (Our Little Sister; Like Father, Like Son), Shoplifters is about nature vs. nurture, the tension between familial belonging and freedom of will. Are we born into a family or do we choose our family? The rich mise-en-scene and powerful performances elevate Shoplifters from a sentimental melodrama to something much more complicated and affecting. Koreeda’s camera is patient and kind, giving gentle attention to particular places and things in this corner of the world.

52. The Lighthouse (2019, Robert Eggers). Robert Eggers’ distinctive vision here transcends conventional categorization–it is a historico-psychological-existential thriller; a bewildering, boozy bloody bromance; a sea-soaked single-location supernatural suspense story. It is, in short, A Lot To Take In. Indeed, nearly every detail of The Lighthouse appears to be perfect. It takes a sort of mad genius to craft such a work of cinematic art.

51. La La Land (2016, Damian Chazelle). At once nostalgic and fresh, La La Land is a vivid smorgasbord of color and life. It nods to classic Hollywood (Rebel Without a Cause, Casablanca) and acclaimed musical directors (Demy, Minnelli) without ever feeling like a caricature. Opening with a remarkable musical number on a crowded Los Angeles freeway, and closing with a fantastic dance travelogue through time, La La Land celebrates (and critiques) the vocational pursuits of dreamers, artists, and romantics. As a dreamer, artist, and romantic, I (still) approve this message.

50. Boyhood (2014, Richard Linklater). Quite literally sculpting in time. It’s better than you remember.

49. Le Havre (2011, Aki Kaurismaki). A filmmaker I’ve only discovered in recent years, the droll comedy of this Finnish filmmaker is remarkable in its application: the present-day European refugee crisis. It’s a decidedly unfunny premise, yet Kaurismaki’s deadpan weirdness and romantic endings are wonderfully endearing.

48. The Rider (2018, Chloé Zhao). Tender, empathetic, and visually rich, Zhao’s contemporary nu-Western both affirms and subverts its generic roots, deconstructing and reconstructing the masculinity, violence, and individualism of the American myth. There is life in this film. I can’t wait to see what Zhao does next.

47. Carol (2015, Todd Haynes). A film I appreciated, but didn’t love, when it was first released—it didn’t even make my Top 25 of 2015—but I have changed my mind upon a revisit. Such a beautiful soundtrack and accompanying images. I’m pretty sure Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett actually fell in love while making this film. A complex and affecting film. Blanchett’s “Ask me things” is one of the best line readings of the current century.

46. Frances Ha (2013, Noah Baumbach). Frances Ha is filled with beautiful, cathartic moments which happen in fits and spurts: Frances sitting with the crying college girl in the dorm hallway; Frances’ monologue telling the woman at the dinner party about her ideal romantic moment, where two eyes catch across the room and there is a “knowing” of each other that is beyond sexual or emotional longing; Frances running and dancing through the streets of New York with a reckless freedom. It is this last image—Frances running—that sticks in my mind the most. The world around her is a blur as she rushes forward, uncertain about the obstacles or opportunities that lie ahead, yet running at full speed. She is the poster child for the millennial generation’s struggles and hopes, rushing with abandon into the future.

45. Ida (2013, Paweł Pawlikowski). The first thing you’ll notice about Ida is its cinematography. Shot in gorgeous black and white and structured in 4:3, every moment is like out of a painting or an old photograph. The story follows an innocent young nun, Anna, on the verge of taking her vows. She goes on a quest with her secular aunt, Wanda, to discover the secrets of her past and the dark history of both her origins and the Polish nation. A coming-of-age journey with a young woman wrestling with identity, spirituality, and her own ontology. Every person has a name, every person has a story, and every person undergoes a crisis of faith in their own way.

44. Selma (2014, Ava DuVernay). Selma is a “Christian” film in the best sense of that term. It doesn’t edit out or avoid the impact of Jesus Christ on Martin Luther King’s decisions. Selma is a powerful film, a haunting film, and an important film. It’s a must-see for pastors in America as we look to examples like Dr. King to be our prophets and the voice for justice. This sounds painfully obvious, but it must be said: racism is still a significant problem in America, and the church has not always been at the forefront of standing for compassion and change.

43. Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010, Werner Herzog). This is one of the only films I can recall where seeing it in 3D enhanced my viewing experience (another film, set in outer space, appears later on this list). A documentary about what is arguably the earliest example of cinema, the Chauvet Cave in southern France is home to the earliest known human paintings, preserved in the cave for over 30,000 years. Herzog offers his own romantic philosophical musings in the narration, which are always quirky and thought-provoking.

42. Personal Shopper (2017, Olivier Assayas). “Haunting” is an over-used adjective in describing films, to the point where it often doesn’t mean anything apart from “memorable.” But Personal Shopper is truly haunting, a ghost story which lingers in one’s conscious, its ideas and questions wandering in the mind like a spirit trapped in an enormous empty house. Count me as a fan of Kristen Stewart.

41. Columbus (2017, Kogonada). Columbus demands audiences to give their full attention, yet this command is given in whispers, not shouts. Each shot is carefully framed, each conversation purposefully paced and wonderfully written with sincerity and pathos. Quiet and deliberate, its form captures the complexity and subtlety of the human relationships it depicts. This is the architecture of human encounters. Columbus is as if Japanese filmmaker Yashujiro Ozu remade Lost in Translation and set it in the Midwest. A beautifully crafted construct in service of its richly human characters.

40. The Assassin (2015, Hou Hsiao-Hsien). The Assassin is deliberately, beautifully obscure. Every image, every character, every movement in the the narrative is in an intentional haze. The Assassin revels in mystery, forcing the viewer to truly contemplate what they’re seeing on screen, creating a tension between the on-screen visual grace and the cerebral work of the audience to understand what is happening before them. You’ve really gotta pay attention to appreciate this film. The Assassin also remains one of the most visually captivating films I’ve ever seen. Hou’s use of color, the framing, the aspect-ratio, all of it; each frame is so deliberate and precise without ever feeling rigid.

39. Drive (2011, Nicolas Winding Refn). A fantasy or fairytale in its neo-noir tone, director Nicholas Winding Refn created something strikingly unique from a familiar arc. Gosling has never been better, and the soundtrack…well…drives. This is a film where image overcomes dialogue; a simple glance between a pair of eyes is infinitely more revealing than any speech or conversation. A superhero film of sorts.

38. Minding the Gap (2018, Bing Liu). In the opening scenes of Minding the Gap, three young men climb the rusted exterior staircases of a derelict building, a tombstone for American industry turned playground for adventurous youths. The men—no longer boys, but not exactly adults—soar on skateboards through the concrete jungle with a sincere prodigality. They are wholly alive as they bob and weave through alleys and down empty parking lots, across bridges and over stairwells. Through it all, the camera hovers like an angelic being, following them with a curiosity and patient energy, as if these young men have its whole attention. This is a literal lens of common grace, a true “God’s eye view” suggesting an empathetic divine presence.

37. Inside Out (2015, Pete Docter). This still holds the distinction of being “The Pixar Film That Made Me Cry The Most In The Theater”. Inside Out is an excellent film about coming of age, the gift of being a parent, and the power of community and friendship. All of these themes are brought together in Inside Out‘s primary idea: the gift and power of all our emotions, even the ones we tend to neglect.

36. Of Gods and Men (2010, Xavier Beauvois). Every so often, a film comes along that merits using “Christian” as a description simply because it beautifully reflects the kingdom of God. Of Gods and Men is such a film. Quiet, solemn, and contemplative, my viewing of the film remains one of the more profound spiritual experiences I’ve had at the cinema.

35. Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010, Banksy). Like My Kid Could Paint That and Summer Hours before it, Exit Through the Gift Shop raises a significant cultural question: what makes art valuable? Perhaps the question behind the question: what is art? Still, the biggest question: is any of this even real? It’s been suggested that Exit Through the Gift Shop is an elaborate hoax, that Banksy is the artist and Thierry is the medium through which he creates this creative prank. If this is true, Banksy’s film is basically a subtle middle finger to movie audiences, much like Haneke’s Funny Games, only far more entertaining. I’m convinced Banksy’s answer to the question would be, does it really matter?

34. The Mill and the Cross (2011, Lech Majewski). I recently went to Vienna and saw Bruegel’s “The Procession to Calvary” in real life. It’s beautiful. Like any masterpiece of visual art, words fail at capturing its beauty. Seek and find this wondrous film.

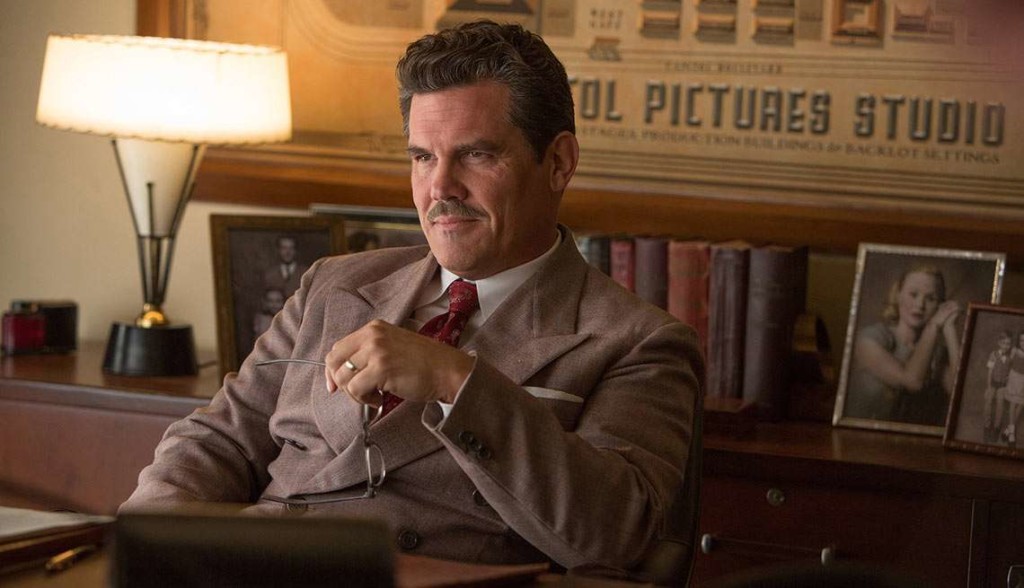

33. Hail, Caesar! (2016, Joel and Ethan Coen). Though I initially gave this a moderately good 3-star rating, my admiration for the Coens’ madcap hagiography of the saints of cinema has gone up considerably upon numerous re-watches. The clergy scene has become a staple in my film-and-theology teaching. Would that it were so simple.

32. Amazing Grace (2019, Alan Elliot, Sydney Pollack). A divine picture of gospel grace, the concert documentary film Amazing Grace lives up to its etymological roots—this is a good film sharing the good news via Aretha Franklin’s supernatural gift of song. If you’re cynical about God, religion, or the church, Amazing Grace is an invitation of healing and hope.

31. Cameraperson (2016, Kirsten Johnson). Having been a cinematographer behind the camera of numerous acclaimed documentary films (Citizenfour, The Invisible War, Pray the Devil Back to Hell, Fahrenheit 9/11), Kirsten Johnson stitches together 25 years of leftover footage–the scraps of the films–into a cinematic quilt. Images juxtaposed against one another draw out themes about the human condition, life and death, and bearing witness to it all through a camera lens. There isn’t a narrative here, per se; this is the essay film at its finest, a personalized meandering through ideas and stories, at once autobiographical and universal.

30. Roma (2018, Alfonso Cuarón). Wish I could have seen this in cinemas, but grateful it’s available on Netflix. This absolutely should have won Best Picture over the mediocrity that is Green Book.

29. Silence (2016, Martin Scorsese). Endo’s novel is one of my all-time favorites, so I went into Scorsese’s film with a sacred wariness. It’s a remarkable work of religious cinema for non-believers, raising critical questions of faith and doubt and God’s presence in a seemingly secularized world. It might be my favorite Scorsese film.

28. Eighth Grade (2018, Bo Burnham). Bo Burnham’s directorial debut Eighth Grade is so authentic in its depiction of early adolescence that it should come with a trigger warning: this will be awkward, and could bring back those stuffed-down memories of middle school you’ve been trying to forget. Adults tend to either ignore middle schoolers or be annoyed by them. But Burnham notices them and pays close attention. And to paraphrase another A24 teen film, don’t you think maybe they are the same thing: love and attention? In this, Eighth Grade is a cinematic act of love honoring those significant years of identity formation by paying attention and being honest, even when it hurts.

27. Sing Street (2016, John Carney). Drive it like you stole it.

26. This Is Martin Bonner (2013, Chad Hartigan). This Is Martin Bonner is filled with these sorts of table conversations, moments of quiet intimacy, authenticity, and depth of emotion. The actors feel so natural and fresh together that it’s a wonder they’re acting at all. They are human, through and through, two men journeying through the sacred ordinariness of life. This is a film about renewed vision, perhaps even a renewed faith.

25. Her (2013, Spike Jonze). This film’s prescience is sometimes frightening with its accuracy. The sci-fi love story between a man and his mobile device operating system is ever closer to being a reality. Every performance in this film is stellar, from Phoenix and Mara (they like making movies together, don’t they?), to Adams and Pratt, and even Olivia Wilde in her few scenes. Yet it’s Johansson’s voice performance which is the strongest here—she manages to make us fall in love with a computer too.

24. The Florida Project (2017, Sean Baker). The Florida Project feels like an episode of The Little Rascals by way of the Dardennes in its handheld humanism and empathetic glimpse into urban poverty. Baker’s camera captures the authenticity of childhood in ways I’ve rarely seen in cinema; innocence, wonder, mischief, anger, grief, brattiness, and silliness are all portrayed by the children here with remarkable comfortability and ease, almost as if the cameras were invisible and recording genuine moments of youthful interactions and reactions.

23. Gravity (2013, Alfonso Cuarón). “Gravitas” means weightiness, seriousness, profundity. Cuarón’s interstellar action drama is more than a survival story, more than a space thriller. Gravity is a meditation on the very essence of life, i.e. what keeps us breathing and moving and continually taking steps into the future. One of the only films where I felt the 3D IMAX experience enhanced the film; yet even on the small screen, Gravity leaves a considerable impact.

22. Gett: The Trial of Vivian Amsalem (2014, Ronit Elkabetz). Gett is like Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation in a Jewish culture, or a marital version of 12 Angry Men. Set entirely in the religious courtroom of Jewish rabbis in Israel, the film is a series of trial scenes; the rooms are stark and worn, like having judicial hearings in the DMV. The color palette is nearly black-and-white, a greyish hue bringing out the paleness of Vivian’s skin and the depth of emotion in her brown eyes. And let me tell you about her eyes, for they are the central feature of this film. So much is communicated through her gaze, and many of the “conversations” between Vivian and her husband, Elisha, are done entirely through glances and glares. A powerful, underseen film.

21. Lady Bird (2017, Greta Gerwig). There’s a line in Lady Bird about love and attention that might be one of the more profound and simple truths I’ve encountered in cinema from the past decade. That they’re spoken by a kindly nun to a troubled teen girl only adds to their significance. A perfect coming-of-age film.

20. The Fits (2016, Anna Rose Holmer). This film is surprisingly divisive—people either seem to dismiss it or praise it, but it elicits strong responses either way. Parables tend to do that, and Holmer’s debut feature film is certainly a parable of sorts. An enigmatic and beautiful blend of the immanent and transcendent, of bodies and spirits, The Fits is both a great coming-of-age story and a cinematic womanist theology.

19. Phantom Thread (2017, Paul Thomas Anderson). Is it appropriate to call this a romantic comedy? Because it’s both a captivating romance and wonderfully funny, even as it remains exquisite in detail and form. I listen to Greenwood’s score on a regular basis.

18. Tower (2016, Keith Maitland). Tragically relevant in our era of mass shootings, this haunting and sobering documentary about the 1966 shooting at the University of Texas remains one both of my favorite documentaries and one of the best uses of animation within a film. It’s a real-life retelling of the Good Samaritan story, and a bit of an ethical Rorschach test, a “what would you do?” in such a dire and urgent situation. As Fred Rogers once said about responding to tragedy: “Always look for the helpers…because if you look for the helpers, you’ll know that there’s hope.”

17. The Immigrant (2014, James Gray). A very strong contender for Best Final Shot in a Film.

16. Dunkirk (2017, Christopher Nolan). Dunkirk is both the quietest and loudest of filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s films. Known for lengthy, cerebral films overstuffed with exposition, Dunkirk is exactly the opposite: lean, action-oriented, even emotional. Driven neither by character nor story, the emphasis is all on the mise-en-scene, image and sound, the immensity of what is right in front of us as the audience, and in front of the characters. A deeply emotional and hopeful film.

15. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018, Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, Rodney Rothman). I keep showing this film to people in teaching and ministry environments because there’s Just So Much to this movie. I’ve watched it five times since its release, and I’ve not exhausted its possibilities and profundity. Simply put, it’s a perfect film. Amazing. Spectacular. Sensational. Superior. I have tried to find faults with it, and I have come up empty.

14. Short Term 12 (2013, Destin Daniel Cretton). This remains the best, most accurate film depicting the ups and downs of youth work/youth ministry I’ve seen yet. Even when it becomes sentimental or melodramatic, it always feels honest. And so much talent in this cast: Brie Larson! Lakeith Stanfield! Rami Malek! Stephanie Beatriz! Kaitlyn Dever! John Gallagher Jr.!

13. The Social Network (2010, David Fincher). A film about smug entitled white guy billionaires and the ubiquitous influence of social media somehow feels even more relevant in 2020 than in 2010. Fincher was robbed of Best Picture and Best Director at the Oscars. The Citizen Kane for the millennial generation.

12. A Hidden Life (2019, Terrence Malick). Attending Cannes in 2019 will be a personal highlight for me from this past decade, and seeing a new Malick masterpiece made the experience all the more significant. A Hidden Life is both the most Christian and the most political of Malick’s films in its biographical meditation on Austrian conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter and his quiet resistance to the evil ideology of his era. A beautiful work of cinematic theology.

11. Before Midnight (2013, Richard Linklater). Hawke, Delpy, and Linklater have taken such a simple premise—two people walk and have a conversation—and created the best cinematic trilogy of all time. Before Midnight is the most difficult of the films for me to rewatch, if only because Jesse and Celine’s relationship is so raw and authentic that their third-act argument feels emotionally devastating. Every time my wife and I watch this trilogy together, it sparks new insights and rich conversations. We too love to walk and talk together. Perhaps we’ll revisit Jesse and Celine in 2022?

10. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015, George Miller). This film is perfect. Perfect in every way. *Sprays silver paint into mouth*

9. Paterson (2016, Jim Jarmusch). In stark contrast to my #10 film, this is an inaction film. Its unique strength lies in its leisurely pace and lack of overt conflict for its main characters. The word that comes to mind regarding Paterson is therapeutic. Every time I watch it is a healing experience for me, a reminder of the goodness in our world and the patience, discipline, and contentment that can be found in both the natural world and the worlds we create in our art.

8. Leave No Trace (2018, Debra Granik). Debra Granik’s masterful Leave No Trace is the very definition of a cinematic parable. A tale of a father and a daughter making their way through the world, the film is striking in its simplicity, yet its generates a genuine sense of awe via its profundity and beauty. In a world which can feel so overwhelming and angry at times, Leave No Trace is a reminder that there is still good in God’s creation, the extraordinary in the ordinary, if we would only have eyes to see and ears to hear. And it’s a Portland film!

7. Upstream Color (2013, Shane Carruth). “Close your eyes.” That these are the first words of dialogue voiced in Upstream Color is not insignificant. Paradoxical in its invitation (what audience would close their eyes to watch a film?) it suggests that the film’s strengths are multisensory, requiring what Vivian Sobchack calls a “synaesthetic” engagement with the film’s body. The film’s structure could be best described as symphonic, with a musicality to the editing rhythms which provide coherence to the disparate images and disjointed sense of time. Yet at its core, Upstream Color is a film simply about healing from trauma of the past and finding hope for the future.

6. Two Days, One Night (2014, Jean Pierre and Luc Dardenne). The best political film of the decade, the Dardenne’s post-secular Good Friday film follows Sandra (Marion Cotillard) on a weekend journey from death into life. Would you take a financial bonus if it meant your co-worker lost their job? What if you were in their shoes? Two Days, One Night puts us in the place of both parties via the Dardenne brothers’ empathetic and enigmatic aesthetic approach. This is the film I typically recommend when people ask where to begin with the Dardennes, as it’s one of their most accessible, and certainly also one of their best.

5. A Separation (2011, Asghar Farhadi). Filmmaker Asghar Farhadi manages to create a strikingly humane and complex narrative surrounding this marital separation in present-day Iran. Every adult character in A Separation is both a hero and a villain, a victim and a perpetrator. Characters’ faces are often framed in windows, looking through the glass, conscious of the invisible barrier that separates them. There is a constant atmosphere of tension, sometimes quiet and unspoken, other times explosive and enraged. The separation between Nader and Simin sets off a chain reaction of events that lead to tragic consequences. The decisions seem simple enough: hire movers to take Simin’s belongings, get a caretaker to watch Nader’s father during the day, etc. But the tiny fractures in the glass of these relationships continues to splinter and spread, continuing to spiderweb until the glass completely shatters.

4. First Reformed (2018, Paul Schrader). Will God forgive us? This is the question raised and repeated in Paul Schrader’s masterful and meditative First Reformed, his first film made in the transcendental style he described over four decades ago. Schrader’s conscious nods to Bresson, Bergman, and Tarkovsky—not to mention David Lynch—place First Reformed in a long-standing tradition of spiritual masterpieces. A cinematic theologia crucis, this would make a powerful double-bill with Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc or Scorsese’s Silence, if one were able to endure (possibly with the help of a concoction of Pepto-Bismol and whisky, Rev. Toller’s favored drink). First Reformed prompted a spiritual and emotional crisis within me; it should come with a warning that it may trigger a dark night of the soul.

3. Moonrise Kingdom (2012, Wes Anderson). One summer while vacationing with my family on the East Coast, we spent a few days in Newport, Rhode Island with some of my wife’s relatives. I remember taking a drive through the countryside in a 1960s-era convertible (the couple we stayed with was quite well-to-do), the gold-and-green hue of the summer light warming everything it touched as we rushed past. Later, while walking through town I noticed a large group of what looked like Boy Scouts milling about the enormous white church in the town square. There were others around too, all dressed in clothes from a different era; it felt like stepping back in time. Then I saw it: a massive church steeple planted on the top of a crushed car adjacent to the church. It was only then that I saw the lights, the wires, the trailers, the headsets–this was a movie production. Elated, I had a picture taken in front of the car-and-steeple, then we strolled away into the rest of our holiday. Months later, I would take my wife on a date to the movies—a rare occurrence, as there are very few films which pique both of our interests—to see the new Wes Anderson film, a romance about misfits and dreams, about biblical allusions and the terrifying wonder of growing up. Then I saw it: the steeple on the car, the red-coated Bob Balaban narrating its significance. And I just grinned. It may be the most delight and nostalgia I’ve ever felt while at the cinema.

2. The Kid with a Bike (2011, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne). The Dardenne brothers’ film I have seen the most, The Kid with a Bike remains my favorite of their films. Which is saying something, as I’ve devoted my academic career to researching their cinema. Indeed, the 2010s will be the decade where my personal vocation shifted from “evangelical youth pastor” to “academic pastor-theologian and film critic,” mainly due to my increased scholarly and cinematic interests, and especially my love for the Dardennes’ films. I remember watching The Kid with a Bike for the first time on my laptop while sick in bed on vacation at my sister-in-law’s house in the Pacific Northwest; it blew me away then, and it continues to do so every time I watch it. This film is one of the best artistic depictions of God’s grace, though it never once mentions religion. I can relate to both Samantha and Cyril, both divine Mother and oh-so-human Son, how the former continually pursues and loves the latter without logic or reason, but simply because it is in her mysterious nature to do so.

1. The Tree of Life (2011, Terrence Malick). Words fail me when I try to describe what this film means to me. A prayer, a poem, a lament, a psalm. Yet it’s so much more—immanent and transcendent, intimate yet cosmological, a work of cinematic philosophical theology which features CGI dinosaurs, I can’t imagine another film taking its place as my all-time favorite. So, let’s watch it together sometime and allow Malick’s moving images to wash over us in sacramental glory.

Honorable Mention: Philomena (2013, Stephen Frears). When I first watched this film in my living room on April 24, 2014, little did I know it would change the trajectory of my entire life. The only way I can describe it is that God spoke to me through this film, prompting me to go on a journey that would eventually result in being reunited with my birth mother and (in a surprise to us all) my birth siblings. A single movie changed my life, and I’m eternally grateful.

Is It Cinema? Award: Twin Peaks: The Return (2017, David Lynch). Lynch’s return to the Black Lodge re-opened the question André Bazin asked all those years ago: what is cinema? If it’s primarily “moving images,” then TP:TR is certainly cinematic. And Bazin’s co-founded film journal, Cahiers du Cinema, listed Lynch’s series as its best film of 2017. Whatever it is, it’s a mysterious masterpiece and one of the weirdest and most wonderful works of art from the past decade.

Thanks for this list. Several of my favorites movies here: PATERSON, LEAVE NO TRACE, THE RIDER, SPOTLIGHT, SHOPLIFTERS, SOMETHING, ANYTHING. So great to see them mentioned. And now I want to watch COLUMBUS, SHORT TERM 12, THE FITS.

Thanks for this incredible list. I am so pleased that you rated “The Kid with the Bike” so highly. It is vastly under appreciated and many have never even heard of it. Same with “Leave No Trace” which was largely ignored. Keep up the good work. God’s Peace!