In July of this year, I got a tattoo. It’s been a lengthy process of deciding what to get and where, but here is the outcome on my right forearm:

It’s a simple combination of a vintage film reel with the European Gothic architectural themes of the stained glass windows of the Scottish Episcopal church we attend in St Andrews.

I wanted something as a permanent reminder of our family’s time spent in St Andrews, where I am continuing in my PhD research on the intersection of theology and cinema with a focus on the Dardenne brothers’ post-secular cinematic parables. The uniting of church and cinema in the tattoo expresses what French film critic André Bazin once wrote: “The cinema has always been interested in God.” I think cinema maintains this theological interest—so many of the films from 2019 have religious themes and theological resonance, asking the big questions about who we are, why we’re here, and what does it all mean. Cinema has the capacity to both be a medium of revelation, as well as way of wrestling with such massive existential questions through image and story, emotion and imagination.

With the end of this year coinciding with the end of a decade, 2019 feels especially nostalgic, a time to look back and reflect. This past year felt particularly significant for my theology-and-film-criticism passions: I attended the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, where I met the Dardenne brothers and saw both Tilda Swinton and Isabelle Huppert in real life; taught a seminary class on theology and film for Portland Seminary; signed a book contract for a monograph on theology and the films of Christopher Nolan; chaired a panel at the American Academy of Religion annual meeting on film criticism; and had my first review pull quote used in a film trailer and poster for The Climb. To list all of the meaningful experiences of this past decade would require an entire book.

Looking at the films that resonated with me the most, there’s a thematic thread of learning how to face death with dignity, about the weightiness of seeing the horizon of mortal existence, relinquishing the past while facing the inevitable future. Whether it’s aging individuals or people confronted with sins of the past or emerging adults truly emerging into adulthood, these are films about maturity and growing up. Earlier this year, the Arts and Faith community created a Top 25 list of films about “Growing Older.” I think many of the below 2019 films could be added to such a list.

Here are my top 20 films from 2019, listed in ranked order. But what is a “top” film? The “best” based on some quasi-objective criteria? A personal “favorite”? Some combination thereof? In short, yes. These are favorites and bests and beloveds. These are the films where the experience was meaningful and affecting, and this affection lingered and endured beyond the initial viewing. These are the films which shared and expressed truth, goodness, and beauty (and often this was accomplished by addressing where our reality has come up short of this truth/goodness/beauty). These are the films that surprised and delighted me, frightened and challenged me, and re-formed my imagination and affections and desires.

The twenty films included are based on US and UK releases. Films I saw at Cannes which will receive a US/UK 2020 release, like Young Ahmed and The Climb, will likely be on my list next year. There are also many critically acclaimed films I’ve not yet seen, such as Uncut Gems, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Pain and Glory, The Farewell, Midsommar, and Waves. If I’ve reviewed the film, I’ve included a link. You can also browse my 2019 Film Journal to see everything I watched this past year. Thanks for reading Cinemayward in 2019, and please keep reading as I celebrate the true, the good, and the beautiful in cinema in the decade to come.

20. Little Joe (Jessica Hausner). An Invasion of the Body Snatchers (or perhaps a Gaslight?) for our pharmaceutical/therapeutical era. In isolation, each individual element—the off-putting score, the idiosyncratic characters (with an exceptional lead performance from Emily Beecham), the IKEA-esque production design, the weird hair—would be just a bit odd, but nothing really frightening. Yet pulled together via Hausner’s impeccable direction, they’re strikingly unnerving, even terrifying. A psychological thriller at its finest. Those little red flowers really get inside your head.

19. High Flying Bird (Steven Soderbergh). A religious film of sorts. André Holland gives one of the strongest performances of the year in this dialogue-heavy indie flick about the insider world of NBA basketball. And Soderbergh shot it all on an iPhone and distributed it via Netflix streaming. Welcome to the new world of cinema.

18. One Child Nation (Nanfu Wang, Zhang Jia-Ling). What begins as a personal search regarding filmmaker Nanfu Wang’s own adoption story becomes a chilling and eye-opening examination of China’s disturbing policies and practices which destroyed so many lives. Just as troubling is Western culture’s blind eye, or even a complicity in the practice—one wonders how many “pro life” American evangelicals have adopted Chinese babies through what is essentially child trafficking. A devastating film.

17. Wild Rose (Tom Harper). Jessie Buckley is a wonder to behold in this film about a Glasgow woman’s dream of becoming a country singer. The music is genuinely great, the story (written by Nicole Taylor) is satisfying, and Buckley is simply incredible. A star is born indeed. The epitome of a feel-good film. Aye? Aye.

16. Marriage Story (Noah Baumbach). The two images that keep coming back to my mind aren’t the Oscar-award-worthy big emotion moments, but near-silent moments: 1) the above moment on the New York subway strongly alluding to the final shot of Farhadi’s A Separation, and 2) the scene of Driver and Johansson working together to close a heavy gate between them. This movie is more than just the dialogue; it’s melodramatic cinema at its finest.

15. Peterloo (Mike Leigh). Perhaps the year’s best political satire can also be considered a historical horror film. Mike Leigh’s richly performed historical drama about the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 is expertly directed; he makes a very talky film about 19th-century English politics both fascinating and heartbreaking. Absolutely maddening to watch, especially the final scenes, but brilliant in its execution.

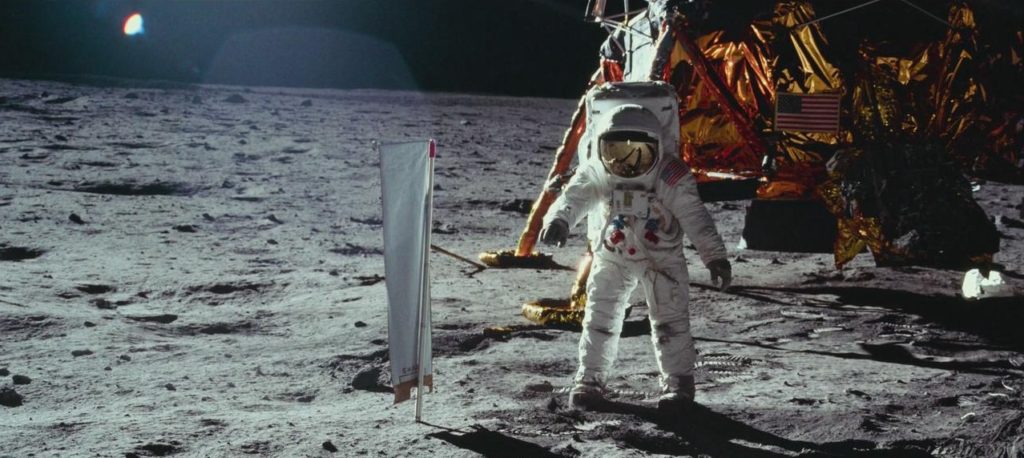

14. Apollo 11 (Todd Douglas Miller). Apollo 11 is a time capsule of wonder. This documentary features some of the best editing and use of sound in a film from 2019, and Miller deserves recognition for his efforts. It’s a trip to the moon we’re all quite familiar with, yet through the immersive images and sound—and there are some shots here which are truly cinematic—it becomes a thrilling adventure film. My three movie-hating children watched the entire thing with me, astonished and enraptured.

13. Transit (Christian Petzold). A purgatorial riff on Casablanca, Petzold’s Kafka-esque film about being stuck in Marseille is initially jarring as it transposes a 1940s Nazi-occupation experience into a present-day context. There’s a dreamy dynamic at work here; it’s almost like a fantasy or afterlife film set within everyday reality. Compelling and romantic.

12. High Life (Claire Denis). The first “Robert Pattinson trapped in an isolated location wrestling with hallucinatory existential dread as he plunges towards the light” film on my list, Claire Denis’s first English-language film is ambitious, reaching for the stars while remaining rooted in earthiness. The film is mostly grim and grimy (and very sexually explicit) but the tender moments between father and daughter as they fly towards a black hole together are genuinely affecting. A philosophical treatise on par with other “Sad Parents in Space” movies (Interstellar, Gravity, Ad Astra).

11. Little Women (Greta Gerwig). Both timely and timeless, this seventh adaptation of Alcott’s beloved novel is a warm hug of a film. Gerwig’s adaptation is true to the spirit of the source material while also offering a fresh cinematic vision. The performances are all compelling, the mise-en-scene is full and refined, and everything is just so lovely and good. The more I’ve pondered the elliptical narrative structure, the more I appreciate it—the movement in time creates a sense of memory and an appreciation of the innocence of childhood in ways a more linear telling might miss. And Florence Pugh as Amy is excellent—she triumphs in portraying the whiny girl who sticks her foot in a bucket for a boy who somehow transforms into a refined Parisian artist.

10. A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (Marielle Heller). There is a scene in Marielle Heller’s wonderful film about Fred Rogers where Tom Hanks-as-Rogers asks reporter Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys) to simply sit in silence for a minute and remember all the people who have shown him love. So they do—and so do we as the audience. The film essentially stops and invites us to remember alongside Rogers, who subtly and suddenly breaks the fourth wall not with his words, but with his compassionate, tear-filled eyes. He looks right at you, at me. To be seen like this, even through a movie screen in a fictionalized version of a children’s TV show…reader, I wept. Like Rogers’s own show, so much of this film shouldn’t work for a modern audience, but it absolutely does.

9. Booksmart (Olivia Wilde). I have a sincere love for teen films, and I haven’t laughed as hard in theaters in 2019 as I did watching Booksmart. Kaitlyn Dever and Beanie Feldstein are wonderful as the snobbish weirdos who learn how to have a wider social life, but Billie Lourd’s supporting role is a scene-stealer, and one of the best comedic performances of the year. Olivia Wilde’s hilarious directorial debut may eventually be considered the iconic “one wild ride” high school movie for the 2010s in the vein of American Graffiti, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Dazed and Confused, or Superbad.

8. For Sama (Waad al-Kateab, Edward Watts). In the midst of the death and chaos of war-torn Aleppo captured by Waad al-Kateab’s confident camerawork, two scenes from For Sama will be forever seared into my memory: 1) smiling children happily playing on a bombed-out bus as if it were a playground, and 2) the cries of a newborn baby boy. Regarding the latter, I don’t think I’ve had a bodily reaction to a film quite like this moment, a jarring emotional oscillation from absolute horror to euphoric joy which left me blubbering uncontrollably. It’s a powerful, harrowing film—indeed, the word “harrowing” just isn’t strong enough. A filmic example of Habakkuk’s complaint to the Lord: “Why do you make me look at injustice? Why do you tolerate wrongdoing? Destruction and violence are before me; there is strife, and conflict abounds.”

7. Light from Light (Paul Harrill). Part of the Nicene Creed says, “God from God, light from light, true God from true God.” It’s a statement about Christology, how the Son of God is both fully human and fully divine in one person. This incarnational mystery, the interconnection of flesh and spirit, is also the underlying tone of Paul Harrill’s radiant post-secular ghost story. Lead actress Marin Ireland is wonderfully restrained as a lonely ghost hunter, communicating a great deal of emotion through her posture and eyes rather than with words (she’s just as good in The Irishman, her second film in my top 10 of 2019). Haunting, in the best way.

6. Parasite (Bong Joon-Ho). Even with all its late-act twists and turns, the Cannes Palme d’Or winner holds up on subsequent viewings. Parasite defies categorization—it’s somehow a suspenseful thriller, a hilarious comedy, a horror film, a family drama, and a scathing social satire all rolled into one. It’s about pizza boxes and peaches and art therapy and Native American headdresses and Chicago and morse code and giant rocks and coffee tables and walkie-talkies and classist systems of injustice. It’s also best experienced with as little foreknowledge as possible. So metaphorical. Respect!

5. Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma). I’m so glad I turned and took a second look at this film, because the initial reservations I wrote about in my review from Cannes evaporated when I paid closer attention—I’d bump this from a 7/10 to a 9/10. This is visual poetry, featuring the two strongest female lead performances of the year from Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel (and they’re definitely both leads). They communicate so much with subtle facial expressions and postures; a lingering gaze, the slight curve of the lips into a smile, a quick movement of the hands. Portrait is sensual without being salacious, wonderfully feminist without being a “woman’s” movie. The cinematography from Claire Mathon (she also shot Atlantics) is stunning, but not in a showy manner; it’s all about the colors and lighting and framing and emotion, about showing the story unfold without having to draw attention to itself. It seems trite and obvious to call Portrait “exquisite” and “painterly” when the film is a French period piece about an artist falling in love, but these are apt descriptions. A slow burn, in the best sense.

4. The Irishman (Martin Scorsese). There is a deep sadness permeating Scorsese’s cinematic memento mori, an inescapable funereal tone. It plays out like a confession, an admission of betrayal and guilt by aging former hitman Frank “Irishman” Sheeran as he tells us of his friendships with mobster Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci) and Teamster Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino). This is a deeply Catholic film: baptisms, grape juice and bread at meals, liturgical repetitions, confessions, etc. “I’m going to church,” declares Pesci near the film’s finale. “Don’t laugh…you’ll see,” he tells Frank. He’s telling us too; we’ll all “go to church” some day and face our Creator. For now, we’re invited into the mediated communal experience of watching and discussing The Irishman, of wrestling with its length and its Netflix distribution, with Marty’s dismissal of superhero films and the lingering question of “what is cinema?” for our hyper-digitized, media conglomerate, streaming service, Tomato-meter era. I once called Scorsese the “priest” of the Church of Cinema; The Irishman is one of his greatest homilies.

3. The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers). Eggers’ hallucinatory nightmare is like David Lynch meets Herman Melville by way of Ingmar Bergman and an acid trip. A thrilling spiral into mental and spiritual madness, everything about the film—from the black-and-white cinematography to the hyper-detailed production design to the exemplary performances from Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe—is perfectly executed. Like the eponymous light itself, The Lighthouse is a film which strangely compels me to watch it repeatedly even if I never want to experience the nightmare again. One of the few films where I felt like I was truly losing grip on reality while watching it. Such is the power of cinema.

2. Amazing Grace (Sydney Pollack, Alan Elliott). This film could make you believe in God. The first time I watched this recovered documentary about Aretha Franklin recording her gospel album, I found myself weeping due to the transcendent spiritual experience. Her voice is heavenly. So when I brought the seminary class I was teaching this past summer to see the film again, I wondered if such an experience was a one-time thing, that perhaps the awe wasn’t sustainable. I was wrong—this is a cinematic sacrament, both profoundly affecting and a rich examination of filmmaking itself. The film’s star is Aretha, of course, but watching Pollack’s documentary team at work is also fascinating.

1. A Hidden Life (Terrence Malick). A cinematic theodicy and the natural culmination of all of Malick’s previous films, A Hidden Life hovers at the horizon of transcendence and immanence like the Spirit hovering over the waters of creation. It is extraordinary precisely because it is so ordinary, a film about mundane farm labor and marital bliss in a quiet corner of the world. Yet there is a weightiness to its images and ideas, a rich sense of the kavod of God, the glory of the Lord. As I noted in my review, this is Malick’s most political film, as well as the most overtly Christian. This is a spiritual search, both a lament and a prophetic work. I would say it’s the most important film for American Christians to watch from 2019—it confronts us with Malick’s question he sent to Martin Scorsese after viewing Silence: “What does Christ want from us?” To paraphrase Bazin’s above quote, Malick’s cinema has always been interested in God. But this view of God is not through ecstatic heavenly visions, but of what philosopher Paul Ricoeur called “the fantastic of the everyday,” or perhaps Jean-Luc Marion’s “saturated phenomenon.” Human hands; church walls; fields of grain; waterfalls; a kiss between lovers. There are traces of the transcendent all around us, if we would only pay attention. Malick pays attention, and invites us to do likewise.

Leave a Reply